Book that provides a roadmap to inner happiness

Team L&M

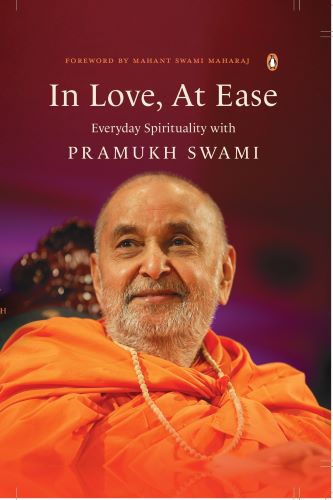

In Love, At Ease Everyday Spirituality with Pramukh Swami by Yogi Trivedi (Penguin Random House) is a definitive biography of Pramukh Swami Maharaj that provides a roadmap to inner happiness and success based on the interactions with a spiritual master. It is a perfect guide to everyday spirituality for people from different faiths and backgrounds through the journey of a spiritual master’s life.

Excerpts (page 137-140)

Chapter – 3 I-Less

A Bold Identity with an ‘i’

Where the Conversation Begins

Even the great Sanskrit and English poets Kalidasa and Shakespeare would have been at a loss for words to describe the view—the pinks, purples, yellow ochres and golden blossoms bursting forth from a canvas of green hills. Monsoon views of the Valley of Flowers in the Chamoli District of Uttarakhand have left many searching for words, and I was no different. Just a short drive and trek from the Hindu pilgrimage town of Joshimath, and an even shorter trek from the town of Govindghat, close to the renowned Gurudwara Hemkund Sahib Ji, the valley brings together visitors and pilgrims from all over the country. It is a popular destination for first-time trekkers in the Himalayas because of its beauty and ease of access. I started on that trek one morning for the same reasons.

I left the hotel with a group of international hikers wanting to gaze at the flowers and streams, but I ended up hiking with an ascetic searching for a wholistic version of himself. We first interacted after the middle-aged ascetic heard me humming a rainy season raga just as it started to drizzle. ‘You sing well, but I recommend you hold off on inviting the rains with your monsoon melodies. It won’t be fun walking through the valley if it is pouring.’ He piqued my curiosity. From his English, I could not tell if he was from India or abroad. From his Hindi, I could not tell if he was from a specific region of the nation. From his confidence, I could not tell if he was a former executive or wandering recluse—or if he was on a journey to becoming ‘I-less’. We exchanged pleasantries. I soon realized that he not only knew his ragas, but also was fluent in several languages, including Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Persian, Arabic, Punjabi, English and Sanskrit. He effortlessly contested Western economic and political systems and Hindu schools of theology. And it was here that our debate picked up pace and intensity.

We discussed Advaita (non-dualism) and Dvaita (dualistic) modes of thinking about creation and Divinity. All through the argument, I kept looking for markers that would point to who he was, what he did, how he identified, what he believed, and why he thought the way he did. I was trying to label him and categorize his various markers based on his outward identity. As we approached the valley, the ascetic kept countering my arguments. I knew that I had to go for the ‘jugular’ argument against non-duality. He would not have a strong response. No Hindu theologian has answered the question successfully over the last 1,000 years, not even the dualists and qualified non-dualists who raised the question in the first place.

We approached the valley as I was framing the argument in dramatic fashion. I expected him to laugh, lose his otherwise relaxed temperament, or change the topic in response. The foot of the valley would also provide the perfect backdrop for my staged final reasoning. The modern-day ascetic, with his salt and pepper beard and tuft, rudraksha beads (stone fruit seeds used for ritual and prayers by Hindus, Buddhists and Sikhs alike) around his neck, a tennis windbreaker covering his saffron and black robes, and all sorts of Christian, Sikh and Islamic imagery in ink on his skin and etched into amulets, gently grabbed my hand. ‘Boy, this is where the conversation begins. You have been trying to place me in a box since the minute we met. Am I a Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, or Christian? Do I believe at all? Am I a musician or a theologian? Was I born and raised in the West or in India? Am I an ascetic or a drifter of sorts? Am I a Marxist or a Capitalist? Am I a dualist or a non-dualist? You have been trying to read and tag my identity for the last fifteen kilometres, while I have been trying to lose that “I” for over the last fifteen years. Minimizing the “me”, “myself”, and “mine” from who I am—replacing the “I” with an “i”—is my spiritual journey. And after travelling thousands of kilometres in these sacred mountains, sometimes I find myself standing right where I started.

This conversation does not end with how I should be identified, what you know, or who won this debate. It begins here. It ends with how we can move past these perceived identities and the sense of existence and even arrogance that they bring. Identity always carries the weight of arrogance. It is that ego that I want to leave behind in the valley, once and for all.’

We sat on a rock at the head of the valley in silence. It certainly was not how I expected to take in the colours of the valley. I am not sure what he was looking at, but I looked out at the flowers swaying in the Himalayan winds, each with a powerful individual presence yet bound by their collective sense of appeal. They were just flowers, but each one added significant value to the valley’s brilliance—each contributed to the beauty that we had trekked all this way to appreciate. There was a portion of their identity they had claimed and another they had forsaken. There was a sense of pride of individuality coupled with a sense of humility, brought on by being part of a larger whole. These flowers were confident and at once, humble. And they impressed me for that reason. The ascetic’s journey, which he considered incomplete, sparked a desire in me to experience that weightless ‘i’. It was the definitive leg of the spiritual journey—the final ‘peak’ to scale. It was a journey that I had up until now wilfully disregarded, for it was a trek much harder than that morning’s hike in the Himalayan range.

There are virtues we seek, and there are those we are content reading and speaking about for they seem humanly unattainable, even unnecessary. Learning to love seems doable and useful. It is a popular lesson among those treading the spiritual path. Learning to realign one’s identity to master humility, tolerance, patience, and even obsequious servitude, seems near impossible. To be ‘I-less’ is to forsake all the pomp and appreciation that accompanies one’s sense of being and existence—one’s ego.