Benoy K Behl

The early river valley civilisation in the Indian subcontinent, from the fourth millennium BCE, was based on a cooperative culture. While there was a sophisticated urban ethos and advanced technology for its time, archaeological evidence has revealed that there was no developed system of kingship or military. The art of the Indus Valley civilisation period was always on a small and human scale; it did not attempt to impress with its size or majesty.

By the beginning of the First Millennium BCE, a second phase of urbanisation began in the Indian subcontinent, this time in the valleys of the river Ganga. The north of India was divided into a large number of principalities, many of which were governed by elected chiefs. In others, the concept of hereditary rule and kingship was beginning to develop.

The Upanishads were composed by the eighth or the ninth century BCE, out of philosophic traditions which perhaps came from the earliest times of Indian civilisation. The thoughts contained in the Upanishads were to form the basis of all major Indic philosophic streams thereafter. In this period, there developed a tradition of asceticism, where the material attractions of the world were shunned in order to seek the truth beyond. The names of two historical ‘renunciators’ of this tradition became most prominent. One of them is Mahavira, who is known as the Twenty-fourth Tirthankara or ‘Victor’ (over the fear of death) and those who follow his path are known as Jainas. The other is Gautama Siddhartha, who is known as the Fourth or the Seventh Buddha, the ‘Enlightened One’ and those who follow his path are known as Buddhists. Both Mahavira and Gautama Buddha taught the philosophy of the Upanishadic age and there are striking similarities in their teachings.

Meanwhile, concepts of state and kingship were developing in the subcontinent. One of the main principalities in North India was Magadha. At the end of the fourth century BCE, under the leadership of the dynamic Chandragupta Maurya, it expanded and is believed to have become the first full-fledged empire on Indian soil. Chandragupta Maurya’s grandson Ashoka is believed to have further extended his empire, to cover the whole of north and north-western India.

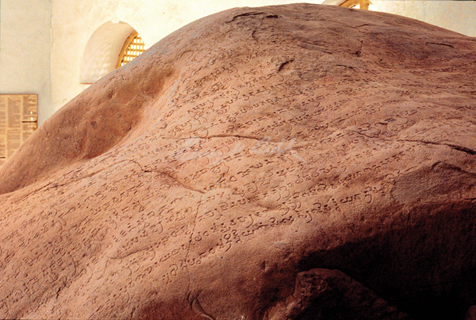

With the introduction and imbibing of concepts of kingship, the art also changed. Instead of the small-scale objects of the earlier period, art was now created to project the messages of rulers. Perhaps following the examples of the Achaemenid Persians with whom Indian rajas had considerable contact, the rulers of the Mauryan period inscribed their messages on rocks and large pillars which they erected for the purpose. But that is where the similarity with the other cultures ends. In keeping with continuing Indic traditions, the inscriptions display that the raja was preoccupied with dharma. Dharma is a man’s duty to all others and the whole of existence around him. The inscribed messages instruct people to follow the ethical path: to respect teachers and elders and much else which is a part of dharma.

Benoy K Behl is an Art Historian, Film-maker & Photographer