Performing traditions are constantly evolving, says Mohiniattam exponent Mandakini Trivedi

Dance costume or the traditional attire for each dance is extremely essential, it make the dance more authentic. Each part of the dance costume has its own significance as well as importance and it even has a reason behind why it is worn by a dancer. Mohiniattam dance costume always intrigued me. So I met and asked my friend Sangeet Natak Akademi Awardee Mandakini Trivedi, who is renowned Mohiniattam guru and researcher about the same. Excerpts from the interview:

What is a traditional attire for Mohiniattam?

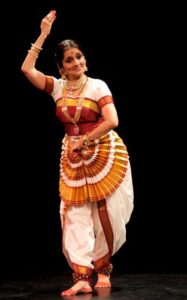

Mohiniattam costume is in stark contrast to other Indian classical dance costumes. It distinctly stands out for its dignified, even austere simplicity. Its uncompromising use of a pearl white fabric enhanced only by a kasava, zari or gold thread border that, in turn, can be embellished with a dash of other colours, is unique in the classical Indian traditions of dance costuming.

This elegant and simple, pearl white fabric, is styled as an ankle length, circular, wrap-around, heavily pleated skirt. A large, pleated fan tied over the skirt, covers the abdomen from waist downwards flowing all the way up to the middle thigh. This ‘fan’, that is probably a hark back to the palm leaf skirts and fans found in the tribal forms like Theyyam, is very characteristic of the traditional Mohini Attam costume. It is enhanced by horizontally stitched, parallel borders, to match the rhythm of the skirt – borders.

The upper half is covered in a saree blouse in white, or any another colour. It is further covered by a pearl white daavani or breast cloth tied around the waist and back.

What about the jewelry and hair?

The jewelry is all gold, in the form of jhumkis, todaas and maatal for the ears, an elakkatali (choker), a kashi maala (long necklace made of gold-coins) gold bangles and a gold udiyanam (waist-belt).

The hair is gathered and brushed to the left side of the head in a bun that is created, in a typical ethnic style, by the use of a hollow, black ring from which the gathered hair is passed and around which it is wrapped. The hair bun is adorned with a string of jasmine flowers. This creates a characteristic and sophisticated, high, hair-knot. This top hair knot is also seen in the coiffure of the royalty in Kerala and was introduced in Mohini Attam by late Guru Kalamandalam Satyabhama.

Is there a historical significance to the that?

Yes, the Kalyanikutti Amma School of Mohiniattam however, does sport a hair-do similar to Bharatanatyam, with the hair tied at the back in a plait and adorned with a gold talai samaan or head ornaments. It is said that in the 19th century, Maharaja of Travancore – Swati Tirunal Raama Varma, invited Bharatanatyam dancers from Tamilnadu to his court, to develop Mohiniattam. This style of costuming seems to belong then.

However, today, the top hair knot is the more popular one among Mohiniattam dancers. Also popular is the side bun with the talai saaman (ornaments framing the forehead and with the sun and moon motifs on either side of the head) in gold or in kundan work. The Padmabhushan, Dr Kanak Rele school of Mohiniattam does not wear the entire talai-saamaan but wears only the chandra or moon motif on the hair bun, to emphasise the feminine quality of the style.

How does the characteristic come alive then?

The multi-bordered, circular fans, the round, top hair-bun and the many pleats characterizing the wrap around skirt, enhance the six characteristic andolita movements of the dance style. These six andolita movements are ghurnavat (circling), dolavat (swinging), prenkhanavat (swaying), tarangavat (undulating), gajavat (elephantine) and sarpavat (serpentine).

You have always been a revolutionary and have introduced a change in the style and costume of Mohiniattam, tell me more about it?

I believe, just as the water is never the same at any point in a river, evTraditions do not fall from heaven. What is ‘tradition’ today, includes what may have, at one point, been the creative expression of a contemporary artist, that has withstood the test of time. Tradition does not mean, ‘no change’. Tradition means intelligent change; change that is organic and rejuvenating.

It is not surprising then that, the costumes of Indian dance styles are also changing. Costumes change to enhance personal beauty. Or, the change may be in response to the requirements of varying aesthetic sensibilities, the requirements of the stage and most significantly, the demands of choreographies.

Where did the inspiration to change come from?

The inspiration came from the native arts like Nangyaar Kuttu, the Kerala mural painting and from the styling found in the paintings of royalty by Raja Ravi Varma. What began as a ‘small’ change in the form of a corset to accentuate the torso and its characteristic andolita movements, was followed by a reduction in the girth of the flared, pleated skirt that seemed to unflatteringly camouflage the sensuousness of the feminine form.

What more did you experiment with?

The introduction of rhythmic foot work, dynamic space levels in choreography, the serpentine leg movements and extensions, even the squat position, coupled with need of sculpt space, incorporating sculptural poses, nudged me to try a dhoti costume.

However, the stark parting of the legs in a dhoti costume while sitting in squat, seemed to take away from the restraint and delicacy of the style. It seemed like a full length, narrow fan, with just a few pleats was necessary, to gracefully cover the space between the two legs. Through trial & error, it was realised that this had to be a sheer/transparent ‘fan’, either made of organza or tissue material, for, an opaque material took away the very feel of a dhoti.

What about the accessories?

I thought why not cover the chest with the beautiful, ethnic, wooden neck piece worn by the Nangyar Kuttu performers? The carved, wooden choker, covered in gold leaf and attached to many strings of wooden, gold bead necklaces, ending in colourful pom-poms, looked gorgeous, grand and ceremonious, transforming the entire ‘look’, giving it an unmistakable stamp of ethnicity, and authenticity. I think the wooden todas or ear ornaments worn by the Nangyaars, can also be adapted and added. Ditto, with the wooden hasta-katakams or bangles that also need to be worked on, to make them less chunky, more delicate.

This work needs to be pursued for, ornaments carved from wood is a typical, indigenous craft of Kerala and wooden ornaments have been in use right from the time of the ritualistic Kerala theatre forms like Theyyam, up to present day Kathakali and Kootiyattam.

Sandip Soparrkar holds a doctorate in world mythology folklore from Pacific University USA, an honorary doctorate in performing arts from the National American University, He is a World Book Record holder, a well-known Ballroom dancer and a Bollywood choreographer who has been honored with three National Excellence awards, one National Achievement Award and Dada Saheb Phalke award by the Government of India.

He can be contacted on sandipsoparrkar06@gmail.com