Tales of love, poverty, crime, and passion

Team L&M

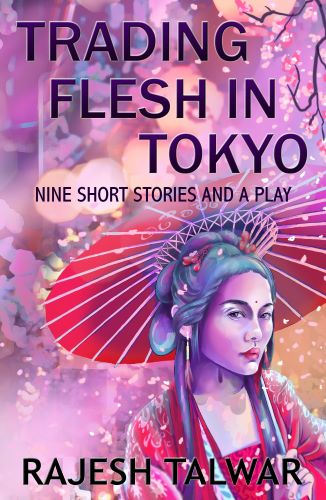

Published by Bridging Borders, Trading Flesh In Tokyo, is a collection of nine short stories and a play by author Rajesh Talwar. The stories deal with love, poverty, crime, passion and various troubling social issues. The characters in the play are powerful non-humans who are familiar to all of us. We bring excerpts from one of its stories, The Price of Revolution, from the book here:

She was a beautiful, long-haired, dusky Bengali girl living with Jyoti Banerjee, a communist revolutionary who spent most of his time crisscrossing the country ‘networking’, as he called it, with like-minded people, trying to bring about a red revolution in the country.

I first met Jyoti Banerjee in Delhi’s District Courts, through Bihari, one of the touts who wander about the court buildings searching for potential clients. Bihari accosted the spindly, balding, middle-aged communist while the policemen were taking him to court. He walked alongside the poor man as the policemen dragged Jyoti through the labyrinthine corridors of the decrepit threestorey building. His hands were tied with rope – they were running short of handcuffs at the station – and after a night in the police lockup he didn’t look to be in very good shape. Owing to his years of experience, Bihari understood immediately, from an appraisal of the activist’s general manner though not from his clothes, that he came from a ‘good family’: in other words, a moneyed family.

Jyoti had been arrested in the act of putting up revolutionary posters in the dead of night, and had been arrested on charges of vagrancy and defacing public property. His younger comrades had managed to escape, but he, being older and slower, was apprehended. He was rather pleased to have been arrested. It confirmed to him several of his views on the nature of the Indian state, which he later told me about at length, after I had managed to get him released completely free of charge. Yes, I filed his papers, appeared on his behalf and secured his release – all this without any payment whatsoever. You are surprised. Well, don’t be.

It was Bihari’s assessment that the boy was from a ‘good family’, and he would ultimately repay us for the pro-bono efforts we made on his behalf. We just needed to be a little patient. Bihari was rarely wrong in his appraisals. Eventually he received a hefty commission and I, I was hailed as a revolutionary comrade. I was invited for a delicious fish curry and rice meal by Jyoti, standard fare in Bengali households, and introduced to his numerous friends and his ailing mother with whom he lived in a first-floor apartment near Gol Market, the circular market near Connaught Place.

Most importantly, I was introduced to Parvati, Jyoti’s girlfriend with the shining kohl-ringed eyes, and we knew from a first glance at each other that we clicked. She was two decades younger than Jyoti – whom I estimated to be in his early fifties – and breathtakingly beautiful. Why did she ever agree to live with him?

Over the course of the next few months, while Jyoti travelled the length and breadth of the country stoking the flames of a red evolution, I paid frequent visits to his home. My visits were ostensibly to enquire about the welfare of his ageing and ailing mother, but in truth I was drawn by the Bengali beauty who lived with her. After several sessions of tea with the mother and her son’s girlfriend – the two were not legally wedded – I sensed that Parvati was warming to me.

One evening while the mother went down to get some biscuits and cake, I held Parvati’s hand and kissed her. After that it was easy. We began to meet every day. She complained if I couldn’t make it because of court hearings. Her attachment to me grew out of the fact that I had aroused in her the flames of a great, but hitherto latent, sexual passion.

‘Jyoti always told me that sex was just a game,’ she breathed to me, after a steamy session, ‘but he was wrong. So wrong.’ Her brow creased in anger as if she was suspecting that he had wilfully misled her. ‘It is not a game. In fact, it is anything but a game.’

I didn’t flatter myself about my sexual prowess, although I thought I did reasonably well in that department. I tried to ascertain the reasons why her sexuality had remained dormant.

‘I think of Jyoti as an elder brother,’ she explained, ‘and he doesn’t look very nice, you know. Especially his teeth.’

While Jyoti was fine featured, he looked his fifty-two years, and his front teeth were misshapen and protruded at strange angles. Nothing a good dentist could not have corrected.

‘I told him about his teeth a few times,’ she said, ‘but he got angry and said these are all bourgeois ideas, about having fine teeth. Communists don’t care about such things.’

After a while I gave up the pretense that I had come to see the mother. The mother accepted my frequent visits and friendship with Parvati as normal. Some days Parvati came over to my apartment in North Delhi, making an excuse that she was going to attend a protest march.

Why did Parvati not join Jyoti in his travels? The reason for this was Maasima, the name we all gave to Jyoti’s mother, who at eighty-eight was half blind and suffered from numerous ailments.

While brave Jyoti tried to create a red revolution in India, it was his young partner who took care of the mother. In this regard Jyoti was hardly any different from the bourgeois nationalist leaders who fought for Indian independence from the British, and whom he always harshly criticised.