Pre-colonial religious sensibilities didn’t differentiate much between Hindu, Muslim traditions, says author Haroon Khalid

Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

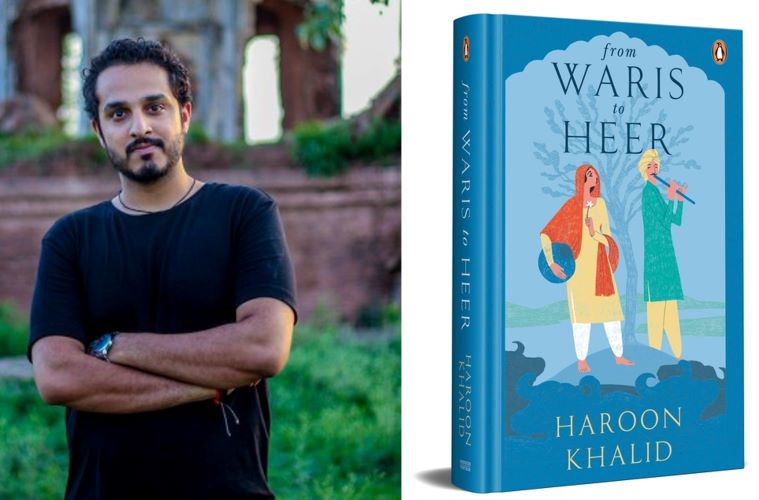

Author Haroon Khalid brings Waris Shah to life in From Waris to Heer (Penguinb Random House), his experimental retelling of Heer and Ranjha. Weaving a story within the story in this book, he successfully portrays what Waris Shah’s life and times must have been in pre-colonial Punjab and how did the story of true love Heer Ranjha emerged in those times. In conversation with Life & More, the Haroon talks about his book in detail:

What motivated you to explore the story of Waris Shah and Heer in your book, and what significance do these characters hold in Punjabi literature and culture apart from it being a tragic love story?

The symbols of Heer and Ranjha are every where. You can quite literally take any Hindi-movie and there’ll be at least one song with a reference to Heer or Ranjha. Within Punjabi Sufi poetry, these two serve the role of being the most recognised symbols, representing a devotee and the divine, similar to Radha-Krishna in Bhakti poetry.

And then of course there are all these movies, Pakistani and Indian, a re-telling of this most iconic Punjabi love legend. But its not just literature, music and films where you find these symbols. Heer-Ranjha are also political symbols. There is a reason why Amrita Pritam wrote “Aj akhan Waris Shah nun” in the aftermath of Partition.

Sardar Udham Singh for his trial in England, requested that he be permitted to take oath on Waris Shah’s Heer instead of any religious book. For me then Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha is perhaps the most iconic Punjab symbol, representing different things to different people and in different contexts.

However, while Heer-Ranjha are the most iconic Punjabi symbol, almost nothing is known about Waris Shah, except for a few details that he mentions in the qissa. We know that Waris Shah wrote Heer at a very important political time in Punjab, the late 18th century. This was the time when the Mughal Empire was dismantling, the Sikh misls were getting powerful, the Maratha were beginning to exert themselves on this region, while Ahmad Shah Abdali was regularly attacking Punjab.

There are references to all these political events in Waris Shah’s Heer. Through this fictional story of Waris Shah, I wanted to firstly make sense of Waris Shah’s life, experiences, influences, etc. but then also see his life through this historical and political context of the time. I wanted to explore how these symbols get represented in Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha, moving beyond the notion that Heer-Ranjha is just a love-legend. It is so much more and that is something I wanted to show through this book.

Please share your insights on the evolution of the Heer Ranjha story over time and its impact on Punjabi literature and society?

The first Punjabi written version of Heer-Ranjha comes from Damodar, who is believed to be a contemporary of the Mughal Emperor, Akbar. That too, like Waris Shah’s Punjab is a time of deep political changes, with the emergence of a rural economy as a result of a more centralized state. So you can argue that Damodar’s Heer was very much responding to those political, economical and cultural changes, much like Waris Shah was responding to 18th century Punjab. Of course, it is highly likely that there were oral versions of Heer-Ranjha prior to this written rendition of Damodar.

However, particularly when we think of Waris Shah’s Heer, I believe there so many cultural and literary influences that exerted themselves on it. For example, you can see a deep influence of the Bhakti tradition and the symbols of Radha-Krishna on how Waris Shah understands Heer-Ranjha. Similarly, you can see the characters of Ram-Sita in these characters.

And not just that, Waris Shah borrows from other folk love legends, from Raja Rasalu, Laila Majnun, and many more. You can think of Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha as a beautiful repository of two thousand years of Punjabi literature, and through this novel I wanted to pay homage to that culture and literature, which is why I was initially calling this book, The Novel of Punjab.

What were some of the most surprising or lesser-known aspects of Waris Shah’s life and work that you uncovered during your research?

A frustrating part about doing research on Waris Shah is there is still hardly anything known about him, except for a few basic details such as the name of his father, where he was born, where he got educated and where and when he wrote the qissa of Heer-Ranjha.

There is hardly any other detail about him. So then writing the fictional character of Waris Shah, I had to fill in that space. I did that primarily by looking at the political context of Waris’s time, asking and then trying to answer questions like, why would Waris have to leave his home and become a refugee, what would inspire him to write the qissa of Heer-Ranjha.

Given the depth of philosophical and religious knowledge, what would his education would have been like?

What was perhaps an interesting feature of Waris Shah’s life for me and something I wanted to learn more about was Waris Shah’s interaction with Bulleh Shah if there was any. We know that both of them were contemporaries and that there were probably in Kasur around the same time. I was curious to know if they ever met? If they did, what would have been their conversation.

While there were no answers to these questions, I could always rely on fiction to fill in the gap. It came as a surprise to me that the figure of Bulleh Shah looms large in this novel, even though I had not planned that initially.

Do you think the story of Heer and Ranjha resonates with readers even today?

Absolutely! I believe that at its core, Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha is a story of gender violence and ‘honour-killing,’ which unfortunately remains a reality in different pockets of South Asia. Waris Shah is very critical of a patriarchal interpretation of religion and customs, to justify gender violence. In this discourse, I feel the character of Heer comes across as a powerful feminist symbol, who really helps us break through the stereotypes of gender roles. Both Heer and Ranjha present an alternative notion of femininity and masculinity, which I believe is quite progressive and resonates quite well with some of the broader conversations that we are having about gender globally, including LGBTQ+ rights.

Heer Ranjha is not just a love story but also touches upon social and political issues. How do you interpret the socio-political commentary embedded within the narrative in today’s terms?

In the prologue of the book I’ve written, “To think of Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha as just a love legend is to render a great disservice to its genius.” I think that along with being a text about love, it is also a political text. In the story Waris Shah beautifully interplays different symbols and characters to make broader points about the political context. For example, there is an interpretation of some scholars that the character of Heer represents a challenge to the status quo, through which Waris Shah is alluding to the Sikh misls that were beginning to challenge the political status quo of that time.

Similarly, there are other characters that become symbols of other phenomenon, like Heer’s father Chuchak, who could be interpreted as a symbol of the political status quo. Taking forward this legacy of Waris Shah, I have also used different symbols from the qissa to represent broader political phenomena. For example, one of my favourite parts of the book is when you have two parallel stories unfolding, one of Ahmad Shah Abdali coming to attack Punjab, while on the other part, you have Saida bringing Heer’s baraat.

How crucial is Sufism and mysticism in the Heer Ranjha story? How do these spiritual elements contribute to the story’s enduring appeal?

The thing about a text like Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha is that you cannot neatly put it into one category of genre. These genres are a very modern concept that don’t necessarily reflect the reality of pre-colonial literature. While being a love legend, a political text, and a discourse on gender violence, this qissa is also a very much spiritual text. And here I believe is perhaps the most beautiful feature of the text. It is very much rooted in a pre-colonial South Asian syncretic religious tradition. It borrows and builds upon several legends and traditions.

Waris Shah’s Ranjha borrows from the Islamic prophet Yousuf, but is also inspired by Krishna, Ram and Shiva. Particularly the second part of the qissa, when Ranjha as a jogi, goes to rescue Heer, is very much tapping on the tradition of Ram going to Lanka to save Sita. Waris Shah doesn’t need to spill that out for his audience. His audience is aware of these various symbols he employs. Waris Shah beautifully quotes Quran on one line and then Gita on the other, and then Mahabharata on the third. These are all part of his tradition. This is the primary reason why Waris Shah’s Heer is loved across the religious divides of Punjab. Particularly in today’s time, how beautiful it is to discover that Ranjha, a penultimate symbol in Muslim Sufi poetry is very much inspired by Ram.

In your opinion, what lessons or insights can readers take away from studying the life and works of Waris Shah, and the story of Heer Ranjha?

I feel like the main thing to take away from Waris Shah’s Heer-Ranjha is an understanding that pre-colonial religious sensibilities were fundamentally different from our understanding of religion today. It didn’t differentiate so clearly between Hindu or Muslim tradition. It borrowed from all and regarded all these traditions as part of its own tradition. In today’s charged political environment, when there are conversations happening about the historical rule of Muslims in South Asia, I feel like it is people like Waris Shah, Bulleh Shah, Shah Hussain, who actually represent the lived experiences and understanding of the broader Muslim-Hindu interaction in the region. They are not the exception to the norm as some might argue.

They were widely popular at their time and continue to be till this day, which goes on to show that their message resonated with the people and that’s how they understood religion. Heer-Ranjha reflects that composite culture and tradition of South Asia that we should be proud of, but something that we have lost today. It is unfortunate that people like Waris Shah have been reduced to the margins of conversation when we talk about Muslim culture in South Asia, whereas I feel that we were right at the centre in pre-colonial times.