Team L&M

Before the abrogation of Article 370, who were the actors in Kashmir theatre of the absurd? The youngsters who could not escape abroad had to play self-destructive roles decided by manipulators sitting in Pakistan. This rivetting narrative delves deep into how Muslim families lost their moorings. A teenaged boy turns to militancy in a desperate quest for employment and identity. A college-going girl is sent to JNU for an insidious agenda of the medicalisation of the intelligentsia. Forbidden love blooms but is doomed.

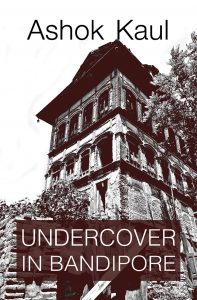

Steeped in history and the truth, Undercover in Bandipore by Ashok Kaul (Rs 371; Pages 360; Vitasta Publishing) holds a mirror to confusion in Kashmir that has been a conflict zone for at least four decades now. The story is told with empathy and passion by the Kashmiri Pandit who is well aware that the exodus of his community was not a triumph for Muslims but an irreparable loss. The modern education they imparted was replaced by rigid dogma. Kaul, Emeritus Professor of Sociology at Banaras Hindu University, weaves a powerful and absorbing mesh of narratives that has, so far, remained untold in stories about Kashmir.

The main protagonist is Barkat, an orphan brought up in Mughal Sarai, by a beggar. During his sojourn in Kashmir, living in the shadows, he discovers that a proud society can be saved only if it takes charge of its own destiny. This is also a dirge for a composite culture that was systematically destroyed. The underlying theme is that nativity in universality is the way out of the morass.

An extract from the book:

Rashid understands the sense of panic. His thirty years of service as an executive in the Power and Works Department in Jammu and Kashmir and deep association with the political elite of Srinagar have kept him aware of the disappointments of this azadi agenda. Even the Hurriyat leaders who run the anti-India campaigns are confused about it. ‘I think that there is no turning back for Hurriyat. Back in 1980-90, they survived in the post-Cold War era, when such movements were treated as ethno-national uprisings. However, changing political developments, both nationally and internationally, have polarised the whole world. The world order is fluid and national governments are no longer held accountable for the perpetual violence. Armed violent movements are no longer considered as ethnic movements but are connected with new agenda of changing the world order on the basis of religion. There is a tacit understanding between the superpowers not to interfere in bilateral disputes.’

Pondering over these concerns, Rashid speaks, ‘Kashmiri Muslims are not like the Muslims of Middle East or even tribal Pakistan. We are not conservative. We practise monogamy and do not have many children, unlike our fellow Muslims across the world. In such a social setup, the current trend of youth perishing in the name of jihad has brought unimaginable despair to the parents who lose their children. Their suffering is unparalleled.’

Although it is difficult for the younger generation to believe, Muslims and Pandits lived together peacefully. Rather than ‘the new game of azadi modern youths engage in, youths of our generation used to participate in various school tournaments

He asks Uzma to convince Bilal to come home at least during the night. His parents have become frail agonising over his whereabouts and probable future. Uzma promises to try his best. The late afternoon brings crimson rays filtering through bare trees and dry leaves in the courtyard, a ‘hum’ vibration adding to the scary ambience. Zoya calls Uzma from the kitchen for dinner. Rashid smiles and they both go indoors. Razia has already set the table for the meal and they all sit down for dinner. Looking at everyone around the table, Zoya wipes her tears and says, ‘I wish Bilal was here too. After ages, I have so many people eating together.’ After dinner, Uzma and his sister go to their room and Zoya cleans the kitchen. Muza and Rashid are left alone.

The silence which prevails most of the time in the house is unusual. It used to be abuzz with activity, as cousins, uncles and aunts lived under the same roof. There was never a boring or dull moment. There used to be a continuous flow of boisterous conversations. Everyone was content and happy. Uzma, who was passing the living area for a glass of water in the kitchen, stopped in his tracks when he saw the look of sheer joy on their faces as they recalled those times. Uzma became curious and sat with them to listen in.

‘Muza, unprecedented changes have taken place since I left Bandipore thirty years ago. I remember how affectionately our elders used to talk, discuss and engage in quality conversations amongst themselves. The daily routine was lively.’ He then looked pointedly at Uzma and said, ‘Although it is difficult for the younger generation to believe, Muslims and Pandits lived together peacefully. Relationships were stable and the course was straight: linearity was taken for granted. Rather than ‘the new game of azadi modern youths engage in, youths of our generation used to participate in various school tournaments. The entire town used to come and watch. We loitered around the Madhumati river any time we wanted and nobody at home ever bothered about our whereabouts. We intermingled culturally without any rancour and divergence but our religious boundaries were intact. Religiosity, if visible, was disliked. Respect was mutual and there was security. These circumstances were not state-given, but were culturally evolved for interfaith accommodation. Social formation had strong roots, where common security, mutual respect, predictability of conduct were the ingredients of the cultural core. It was the strength of our culture’.