‘Women with disabilities have to fight hard to just be recognised as women first’

Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

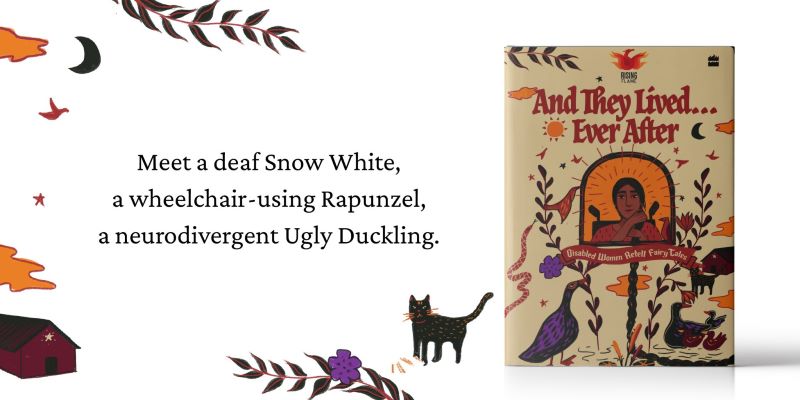

Rising Flame, an NGO working in the disabled space, recently published a book And They Lived… Ever After. The book is a collection of 13 fairy tales we have grown up reading, but with a different twist. These stories are written by authors facing one or the other disability in their life, and authors have also inter-woven their own life experiences in these tales. In conversation with Life & More, Founder and Executive Director of Rising Flame, Nidhi Goyal speaks talks at length about how the book came about, her life and more. Excerpts:

What’s the idea behind coming up with this book, And They Lived Ever After?

Persons with disabilities do not find themselves in stories. When we say we, persons with disabilities, are invisible, we mean to say that we are invisible in data, in society, in policy programmes, laws, and more importantly, in stories. And it really starts from there, when there is no representation, or even worse, incorrect representation, it reinforces the invisibility, it reinforces the stigma around persons with disabilities.

Have you ever picked up a book and most of the popular stories, even cinema, if you see, basically the wicked person would either have a hunchback or have a prosthetic foot that makes an ominous sound, or an eye patch or humour is generated when someone cannot speak.

Humour is also generated with neurodivergence in many stories. We take persons with disabilities as either someone who does not exist or as objects of fear, humour, charity, pity, and this is basically what we wanted to change, and hence the idea of the book.

What was the criteria behind selecting the authors?

It was a process. We wanted to come up with a collection in South Asia because such a collection by disabled women has not been there. Reclaiming these spaces, reclaiming popular tales, and particularly reclaiming fairy tales, which have a very strong gender angle as well, was very important for us.

So, we embarked on this journey, a process of hosting a workshop, a creative writing workshop, where we invited award-winning author, Aditi, as the facilitator. What we basically did was opened up applications for women with disabilities, women and gender-marginalised persons with disabilities across South Asia, so that these stories, when they are being reclaimed, have the nuances of the experiences of people that stand at this intersection of gender and disability.

The selection was like any other selection process, an open one. Applications were received, shortlisted, and the final candidates were invited to be a part of another workshop.

In this workshop 19 to 20 women with disabilities participated; it was a fully accessible inclusive space online with sign interpreters, live captioning, you know, breaks built in and so on and so forth. Because this was during the pandemic in 2020, it was fully virtual.

Thirteen women with disabilities were then selected, and they would write their stories that were then reviewed. And after the entire review process – peer review, review by the facilitator, the team, et cetera, we hired an editor for the job. And then, we took this collection to HarperCollins.

It took us a little over three years to bring this book together.

Who is your target audience?

Well, everyone out there is our target audience, especially the young adults. This book would resonate with everyone because fairy tales or popular tales have been a part of our lives since long. And so, seeing a different perspective, seeing the shift is important for all of us. But the beautiful and unique part of this book is that while we’re learning and unlearning about a community, we’re also learning, unlearning and exploring different worlds through the experiences of women and gender marginalised persons with disabilities; we’re also sitting back and finding ourselves in these worlds. We’re coming to know or discovering experiences that we may not have known, not just in our personal lives, but through cinema, through other things, et cetera, in our circle of worldview or exposure.

We may not have seen all of this, but what is really important is that the feelings, the emotions that are put forth of the hesitation to belong, or the sense of isolation, or asserting one’s independence and freedom, negotiating with friends, the feeling of being forgotten are known to us.

Do you plan to bring up more books from the disabled section?

We have been, and we will continue to put out stories of those who remain unheard, unseen and don’t find enough space in society. We have been working on bringing our books, booklets, stories, narratives, through our various initiatives. Through our research, publications, social media, and our YouTube channels, we have been bringing out stories and amplifying voices of persons with disabilities and focusing on women and youth with disabilities because that’s what Rising Flame does. We have created books which combine experiences of women with disabilities in the #MeToo movement. And that’s a book where it brings global experiences together. We have a book where young women with disabilities have written about romance, relationships, love, abuse, rejection, etc. And that collection is called Dil Vil Pyaar Vyaar or From Shadows to the Centre.

Why was Rising Flame set up

It was born out of the need of community. You see, I live with a disability and I acquired this disability when I was a teenager. Since then while I was continuing to lose my sight, I kept seeing more and more clearly about what the community or other persons like me, other women like me needed in their lives, everyday lives.”

I then started working closely with the community and set up Rising Flame in 2017. I went through a series of names. I wanted a name that would represent us as a community as also our spirit with the honesty, integrity and dignity. A name that spoke about not just the potential, but also the leadership. And hence the name Rising Flame. Flame symbolises change, transition from stigma to awareness, from darkness to light, from exclusion to inclusion, and Rising, it is for people with disabilities to rise, to grow, and to lead from the front.

Please brief us on the various initiatives that Rising Flame has taken up so far

Rising Flame and its short life of seven years has created a huge impact and brought forth leadership of persons with disabilities and has been focusing on the rights and inclusion of particularly women and youth with disabilities. We have run multiple programmes, projects, organised events, made policy interventions, published research, and many that have been landmark in changing the way persons with disabilities access rights and opportunities. The main twofold strategy of Rising Flame under which all of these activities fall is to first, empower and enhance the capacities of persons with disabilities, particularly women and youth. And then, influence the ecosystem which also means that persons with disabilities live in society. Social integration or inclusion cannot be successful only by the efforts of disabled people. We need to create an ecosystem. We need to make other people aware. We need to train them. We need to ensure that professionals, policymakers, everyone from professionals to policymakers, from businesses to institutions, everybody builds an inclusive approach and that is what we do through our campaigns, events, awareness, research and policy, policy interventions, but also research publications, research and other publications.

Some of our key programmes is what we call the leadership bucket. Like one of the programmes, the National Leadership Programme for Women with Disabilities, which is called I Can Lead, is the first of its kind in India at the national level, which recognises their potential and commits to investing in them.

What all kinds of disabilities do you cater to?

We’re a cross-disability organisation, but the beauty of our organisation is that we are a self-led team, which means that the team is from the community itself. Majority of us live with a disability, chronic illness or mental health condition And so we really walk the talk because we believe in nothing about us without us.

What kind of discrimination do people with disabilities face?

All kinds – big and small, discrimination in attitude, behaviour; discrimination at the institutional and policy levels.

The everyday discrimination starts from home, where families may feel ashamed or there is a whole guilt and shame associated with a member living with disability.

The discrimination in schools where students with disabilities struggle to seek admission.

Discrimination in access to opportunities where educated persons with disabilities are struggling to find jobs because companies do not want to hire them or provide them with the necessary assistive devices and supportive environment to function and to thrive.

Discrimination in promotions. Discriminations in law where we are still using words in many of the laws in the country like ‘unsoundness of mind’. laws that discriminate against persons affected with leprosy and so on and so forth.

So, discrimination is at multiple levels, and we need to work holistically on all of these discriminations to make an impact. At one level or the other and often people fight saying once you change the law there is a constant conversation or discussion that once you change the law people will change and on the other hand it’s said once people will change the laws, policies and implementation will change but we think both sides and all sides need to collectively make that effort because inclusion is not just the responsibility of persons standing at the margins, persons with disabilities.

Is there discrimination on the basis of gender as well amongst people with disabilities?

Yes, when one stands at the intersection of gender and disability, the barriers become much more complex. Women with disabilities, have to fight very hard to just be recognised as women first. They are not recognised as women by people, by society. Ungendering is a very common experience, and why? Because we have gender stereotypes around women. We think that women should be caregivers of the family. And the minute a disabled woman like me seeks some support, there is a question saying, oh my god, but she needs help, so she may not be a caregiver. And hence, she will not be a woman enough. The ideas that disabled women cannot be mothers, cannot be caregivers, cannot be parents, cannot be providers and families, cannot be earning members, but also cannot be cooks and everything else that’s expected out of women, the assumption that they cannot be and the need constantly that women should be all of this to be recognised as women enough is constantly there.

You know, many families don’t report that they have a girl child with disability. They either choose to hide the disability or the child entirely. In census and other data collection, surveyors should be trained in such aspects and disability questions must be included.

Why girls are discriminated more? Because there is some expectation of some sort of perfection from women, that they need to look a certain way, act a certain way, and be, quote unquote, perfect, and to bring pride to the family. Any difference or deviation is considered as bringing shame to the family. Sadly, women with disabilities are really at the bottom of the social rung.

In our report, a first of its kind in India as also the world, Neglected and Forgotten: Impact of COVID Crisis on Women and Girls with Disabilities, you can see that in low resource settings, when there was just one mobile phone available and it was remote learning, or remote education, online education then the non-disabled child was prioritised over the disabled child, and if there were two, disabled children, then the boy child with disability was prioritised over the girl child with a disability.

How has the scenario changed over the years?

There has been some progress. In 2016, we had the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act. We had some amazing laws, and I would like to look at the decade, to look at some of the criminal laws that have been amended and so on and so forth. Companies are becoming more aware because of collective efforts. There has been progress, but it’s never enough. But, even today, a non-disabled person would have access to 10 e-commerce platforms, while a disabled is still not seen as a customer. A disabled is not seen as someone who has the capacity to pay or is running a household or is leading an organisation because these e-commerce sites, the payment gateways would just not think about accessibility. There are limited options and society at large wants us to be contented with that. My question is WHY?

How much help comes from the government?

The government is doing some bits, society is doing some bits, and so to respond I just want to say that unless we make it a commitment, unless inclusion becomes a commitment nothing major can happen.

Why inclusion is so important? You would ask. Even if we move away from human rights, just look at it in business and economic terms, the exclusion or the cost of exclusion of persons with disabilities can cost a country as much as seven per cent of its GDP? So, we are looking at something that is important, and is crucial for all round development of all of us.

What are your expectations from the government, as well as society for this sector?

Both must commit to the cause of inclusion and acknowledge persons with disabilities as persons first, equal people, equal human beings, and equal citizens of the country. Once we do this, we will be able to move ahead, and bring disabled into their everyday lives, into their businesses, into their interactions, into their constructions, into their infrastructural efforts, into everything that they do.

How is it being India’s first disabled stand-up comedian, please share your experiences, any anecdote that you have still not forgotten?

Actually, when I started performing comedy, I had not looked at myself as India’s first female disabled comedian, like a woman comedian who is disabled. It was pointed out to me by a journalist actually. He said, “You are India’s first disabled comedian, female” and I was like, “oh yes I didn’t think about it like that” and then I got a little sad. I thought why don’t we have enough of us? Why is it so rare, right? And it is challenging to be

India’s first female disabled comedian. Forget about first, just being a woman and being disabled and being up on the stage because the first five seconds is silence. The first five seconds, people are thinking “What is she going to do? How will she make us laugh?” right? And the conversation then shifts from there. So where other comedians start from 0 or a clean slate, I am starting from minus because people have those ideas around disability, around women. And I have to move up to making them laugh, to reach the humour index of 70-80, etc.

What my stand-up comedy does is that, through my life stories through my life experiences, and experience is of people like me. I just do what other comedians do, I bring these life stories in a humorous fashion to the table, and through- by looking at the humour in the stigma around me, looking at the humour in the ableist behaviours around me, I am able to tickle the bones of people in the audience but also make them reflect.

I would like to share two interesting incidents.

In my first ever show, my debut in Calcutta, the first remark that I got was amazing because this woman was really laughing. After the show, she met me and said “Listen I was laughing so much. I was falling of my chair but at the same time, I was also cringing because I realise that do some of these things with persons with disabilities or I believe some of these what you have presented I also hold those stigmas.”

The second incident. the second reaction was after my first TEDx talk. This was in Delhi NCR, and I remember this man came up to me later and said, “Oh my God you are very bold haan?” And he laughed a little uncomfortably. I didn’t think it was really a compliment. It was a discomfort wrapped up in words by saying that you dare to be bold in spite of being a woman and in spite being disabled. And that was not necessarily coming from “Oh wow, you dare to be bold” right?

I do many private shows for teams and cooperates and other and that really hope to continue because this is a medium that brings awareness through humour and I am very excited about it. It brings me a lot of joy to be calling out the elephant in the room.