Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

Archana Soreng comes from the Khadia tribe. The passion towards Nature and environment she got in her genes – her grandfather pioneered the community led-forest protection in the village he lived in Odisha’s Sundergarh district while her father was an advocate of indigenous healthcare.

After graduating in Political Science from Patna Women’s College, Soreng did her Masters in Regulatory Governance from Tata Institute of Social Sciences. During this time she also began studying environmental regulations, only to find that many of the practices and ways of life of “adivasi communities recorded in textbooks were not written by the community members”. That was when she realized that it was important to “speak, write and share about our perspective and worldview through our own lens”.

Soreng is one of the 17 youth climate heroes chosen by the United Nations in India for its project We the Change that aims to showcase pioneering climate solutions as a celebration of India’s climate leadership in the run up to the UNFCCC’s Conference of the Parties (COP 26) which will be held in Glasgow in November 2021.

“Tribal communities have been at the forefront of protecting the forests and Mother Nature through their way of living, their traditional knowledge and practices, even at the cost of their life. They are the ones who are most adversely affected due to the impacts of the Climate Crisis. Thus, we need to make tribal communities an integral part of the decision making process of Climate Action,” she says. In conversation with the Life And More, Soreng talks more about her work with and for the tribal communities:

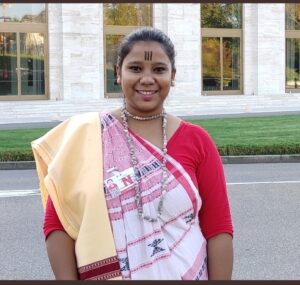

Archana Soreng

How did you get interested in working for tribal communities?

I was working with TISS in 2017, when I lost my father. His death made me aware that the leaders and elders of our community will not be around forever. It triggered in me an urgent need to learn traditional practices and document them. It is only through documentation that upcoming generations will know about these practices. This motivated me to delve deeper into writing and documentation, to work on the Indigenous issues and their contribution towards climate action and the conservation of biodiversity.

What is the expanse of your work with the Khadia tribe?

I work as a research officer with Vasundhara: a policy advocacy organisation that works on natural resource governance, biodiversity conservation, sustainable livelihoods and climate action. With Tribal Youth Groups, we have discussions on how important it is for us to know about our community, traditions, cultures and knowledge systems.

I am also a part of an Initiative called Adivasi Drishyam where we create several videos on indigenous songs, medicines etc. and upload them on YouTube. It is important to understand that it’s not just about documenting these practices but to consider the format in which they are being documented as well.

Do you only work with Khadia tribe of Sundergarh or there are others?

I work with numerous tribal communities like Kondh, Oraon, Santhal, Paudi Bhuiya, Ho, Munda and others apart from the Khadia. Due to this, I realised that even though every tribe is unique, there exists a consistency, an underlying thread that links them together. Their cultures are sustainable and respectfully intertwine with the Nature. Each tribe protects Mother Nature, but

How do tribal people solve the plastic problem?

In many ways. For example, they collect leaves from the forest and then stitch them together with splinters to make plates. They use grass to make chairs, coconuts to make resistant ropes for beds and twigs to brush their teeth.

Because all these materials are biodegradable, these can be an alternative to plastic, which can be adopted by the people in the cities.

Unfortunately, a lot of these ideas have been hijacked by others, and tribal communities do not receive the credit due to them. Even when their products are purchased by retailers, they receive a very low compensation compared to the final price at which they are sold to customers. As the world slowly shifts towards a more sustainable model, tribal communities must be recognised for their input and be supported so that they can play a bigger role.

Interaction with the people of Dhukamunda village.

Isn’t it important to mainstream the adivasis…

Absolutely, and we are working towards that. Under the initiative Adivasi Drishyam, we create videos on indigenous songs, medicines etc. and upload them on YouTube. We firmly believe that it is not important to just document these practices, but document them in various formats. When we just write about them in articles or even books, we are restricting the reach of the content, but when you share images or create videos, they are available and accessible to people who have not received formal education. Plus, there is the added benefit of the content being present on various platforms.

I believe in order to incorporate these practices at the policy level, government entities and organisations must put in effort to research and document these practices and the impact they have in an institutionalised manner.

I live in Odisha, so I can write about what is happening in the state, but what about the other states? I will not know what is happening there. Collective corroboration is very important, and only when something is documented can we make it a part of the policies.

What is the role of tribal communities in preserving forests?

Back in the 1980s, when illegal timber logging groups – commonly known in India as “timber mafia” – were devastating the forests in Nayagarh District, men from the Kondh Tribe would patrol the forests, often sparking confrontations with the loggers. To avoid conflict, women were asked to come along during patrols. Since India’s laws against attacking women are harsher, they would act as better deterrents. But very rapidly, women successfully took over daytime patrol shifts.

So, for the past 40 years, they have protecting forests. The sound of sticks hitting together is enough to send any illegal logger run for life. They know women will catch them if they don’t escape. The protection of these forests has also helped restore the soil that had been eroded due to deforestation affecting cultivation.