HEART OF THE MOUNTAIN

Nashik caves. Pic. Benoy K Behl

Benoy K Behl

It was the 2nd century BCE, the Shunga period in Indian art. Great Buddhist stupas were being made at Bharhut and Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh. Motifs and traditions which were to prevail in Indian art were being established here. In the meantime, another great chapter of art was opening in Western India. For over a thousand years, from the 2nd century BCE onwards, more than 1200 caves were excavated out of the mountains of the Western Ghats. This tradition may have been inspired by the caves excavated in the 3rd century BCE by Emperor Ashoka and his grandson Dashratha at Barabar in present-day Bihar. Those were made for the Ajivikas, who were a deeply ascetic sect. While secular buildings were being made of ephemeral materials like wood, that which was made in service to the eternal was carved in the heart of the mountain itself.

The first phase of prolific excavation was from the 2nd century BCE till the 3rd century CE. Great Buddhist prayer halls and Viharas for the residence of monks were made under the rule of the Satavahanas and the Kshatrapas. Individual sculptures and pillars were donated by merchants, bankers, gardeners, farmers, fishermen, housewives and others, including many who were Greek. These cave sanctuaries were all made on the caravan routes which came from central India to the ports on the coast of Maharashtra.

Perhaps it was the great prosperity on account of flourishing trade which made possible this era of magnificent rock cut caves. Trade networks, both internal and with the Mediterranean were expanding fast in this period. The Roman historian Pliny the Elder writes in 77 BCE that Roman coffers were being emptied for buying too many fine textiles from India.

On a high hill, a grand Chaitya-griha and Viharas were created in the 1st to 2nd centuries CE at Karle. This is the largest of all Chaitya-grihas to be carved out of the living rock. One must remember that these magnificent Chaitya-grihas are not architecture really, but sculpture on an epic scale. For the Indian artist, the rock contains in its heart the divine. It is for him to but remove that which hides the image from our sight: to reveal the sacred nature of the hill.

One can imagine how vast the task must have been to create such rock-cut shrines. The cutting of the rock began from top to bottom and front to back: creating the spaces and leaving stone for pillars to be shaped later. Even as the stone was hewn to create the structures, the finishing of the walls and the carving of detailed sculpture was taken up.

The façade has on it six couples, larger than life and filled with robust vitality. These are the yakshas and yakshis who embody abundance and fertility of nature: the forces that ensure the continuity of life.

They were seen individually in the gateways of the stupas of Bharhut and Sanchi. Here they have come together as mithunas, or loving couples. Their closeness to each other in natural affection symbolises the completeness of the world, of the harmony of the natural order. These are idealised human forms, presenting the symbolic essence of human life at its most vital. They graphically display the quality of prana, or the inner breath, of Indian art.

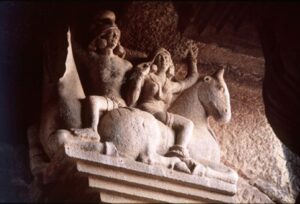

The grand hall is 124 feet by 46 feet and rises to a height of 45 feet. The pillars along the sides have purnaghatas or ‘vases of plenty’. The capitals have seated animals, carrying human figures. The ones facing the central passage are superbly rendered elephants. Each carries two onlookers, usually a couple and sometimes two women. They are seated in a friendly embrace and display a rare warmth. Inscriptions record the names of numerous individual donors who paid for the carving of various parts of the cave and its pillars.

In the Shunga and Satavahana periods, from the 2nd century BCE till the 2nd-3rd centuries CE, were formulated the themes and traditions of Indian art. There was a common artistic tradition and the same motifs in Buddhist and Jaina art. These included Yakshas, Yakshis and the deity Lakshmi. While stupas with sculpted railings and gateways were made in Central India, great rock-cut caves were excavated in the hills of Western and Eastern India. The exteriors had images of the life of nature. Deep in the silence of the mountain was simplicity itself. A symbolic representation of the escape from the illusions of the material world.

Under its series Glimpses Of Culture, India Habitat Centre is presenting a talk by Art Historian,

Film-maker & Photographer (and the author of this article) Benoy K Behl today (January 27) at 6pm.

A film ‘Heart of the Mountain’ (produced by Behl for Doordarshan)

will also be screened on the occasion.

Click here to join