Mamallapuram: Period of Transition

Benoy K Behl

The 7th and 8th centuries at Mamallapuram are a remarkable time. The humanistic and naturalistic qualities of ancient art are continued here in the rock-cut sculpture. At the same time, we see here the beginning of structural temples. At Mamallapuram, we also see the start of royal patronage of temple-building and the earliest royal portraits.

On the shores of Tamil Nadu, on the eastern coast of peninsular India, is a marvellous town of temples, carved out of the rock. Mamallapuram was one of the greatest sea-faring ports of ancient times. This port town was called Mamalai, or ‘Great Hill’. Ships sailed constantly from here to Sri Lanka, South East Asia and China.

Narasimhavarman I changed the name of the port to Mamallapuram or ‘City of Mamalla’. The bustling town would have had a great cosmopolitan culture. Coins found here testify to extensive trade with Rome and other places, as early as in the first century. In its markets, people from South East Asia would have rubbed shoulders with Romans.

Here, over perhaps a hundred years, from about 630 to 728 CE, marvellous monuments were cut out of outcrops of hard grey granite. Cliff faces were transformed into a teeming world of animals and people. Boulders were carved into fine temples and rocks were chiselled into the shapes of animals.

The magnificent temples of Mamallapuram reflect the range of fully-developed styles of south Indian temples.

Facing the ancient port and not very far from it, is one of the marvels of the sculptural art of India. The face of a vast granite rock, almost 100 feet by 50 feet, has been transformed into a world of divine and earthly beings. This giant relief is believed to be of the early or middle seventh century. This tableau presents the auspicious moment of the descent of the river Ganga, to bestow her blessings and her treasure of fertility to the world. Some scholars have also interpreted this scene to be of the penance of Arjuna, the hero of the epic Mahabharata. A deep cleft in the rock has been artfully used to represent the great river, as she descends. In fact, a storage tank has been made above it. On ceremonial occasions, water must have been let out to rush down the cleft, giving a sense of reality to the sacred scene.

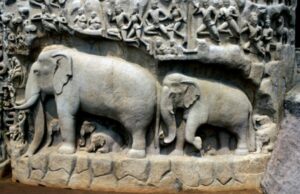

The overflowing life of a forest has been created around the river. About a hundred figures of animals, men, women and divine beings can be seen around the river. All turn in reverence towards the life-giving river. All of these are approximately life-sized and are made with great sensitivity and naturalism.

The realism and life-like softness of the elephants is remarkable. The details in the depiction of the baby elephants show the artists’ deep concern for all the beings of the world. Another detail of a deer scratching its nose shows great sensitivity and a keen observation of the natural world.

At a short distance, is another rock-cut relief depicting the same subject. However, it is unfinished. A little to the left of the great ‘Descent of the Ganga’, the scene of Krishna Govardhana is carved out of a boulder. Lord Krishna holds up Mount Govardhana to protect the village from the fury of a storm. It is a charming scene. With peace restored and the storm forgotten, a cowherd plays the flute, while another milks a cow. This is one of the finest depictions of rustic life in Indian art.

The scale of the figures sculpted by the artists of this period is naturalistic. A sense of depth is imparted to the panels, through the depiction of a variety of postures. Some turn inwards while others are presented in a rear view. Such arrangements of figures were also seen in the paintings of Ajanta of the fifth century and in the art of the Krishna Valley in Andhra Pradesh.

One of the most magnificent sculptures in Mamallapuram is that of Mahishasuramardini, made in a seventh century cave. It is significantly different from earlier representations of this subject. Durga, battles the Mahisha or demon buffalo. It is an animated scene and, unlike earlier depictions of this subject, here the scale is naturalistic. The demon has a human body and the head of a buffalo. The natural poses of the figures, advancing from one side and pulling back on the other, enhances the drama and realism of the subject. The self-assured ganas of Durga’s army of righteousness are unforgettable.

Mamallapuram is also renowned for nine monolithic free-standing temples, cut out of boulders at the site. Five of them are grouped together. These are the earliest such edifices in India to be carved both on the outside and the inside, out of living rock. They are popularly called rathas or temple chariots. This is a misnomer as they are meant to be temples. These sculpted monuments are a marvellous record in stone of the many forms of temple architecture in south India at that time. The monoliths are today named after the five Pandava brothers from the epic Mahabharata and their common wife Draupadi. They form a coherent group and were probably made in the middle of the seventh century.

Built right next to the lapping waves of the sea, one of the glories of Mamallapuram is a temple with two towers, known as the Shore Temple. The finely worked and slender towers are among the most beautiful of any structure in the Indian sub-continent. The temple was probably made by Narasimhavarman II or Rajasimha in the early eighth century. He is believed to have established the tradition of building structural stone temples in Tamil Nadu.

Over 1,200 years of salt-laden winds have taken their toll and the profuse sculptures on the temple have been considerably eroded. However, what remains shows the highest standards of artistic achievement.

Perhaps the most memorable aspect of the art of Mamallapuram is the depiction of the many beings which inhabit the world around us: the deer, the cows, the elephants and others. Man is seen amidst the world of nature, as one of its many manifestations. The Indian sculptor manages to communicate the living, breathing quality and emotions of animals with a rare empathy. What gives the art of ancient India a special place, is its vision of the world which sees the same in each of us, men and women, in animals, plants and trees. It sees a unity in the whole of creation, thus imparting a great sense of harmony and compassion to this art.

Under its series Glimpses Of Culture, India Habitat Centre is presenting a talk by Art Historian,

Film-maker & Photographer (and the author of this article) Benoy K Behl today (May 25) at 6pm.

A film ‘Mamallapuram: Period of Transition’ (produced by Behl for Doordarshan)

will also be screened on the occasion.

Click here to join