On the eve of World Dance Day, renowned Bharatanatyam dancer Geeta Chandran says very few people go to enjoy the ananda or rasa of a dance performance these days

Over the past six or seven decades, in India, despite the best efforts of various organisations – government and others – the audiences for classical arts – especially a stylised classical dance form like Bharatanatyam – have qualitatively dwindled considerably, even while their aggregate numbers may have grown. This is because today there is no natural audience for Bharatanatyam, since classical dance is not purviewed as necessary entertainment by the audiences. This has led to a loss of quality among dance viewers – the rasika (cognoscenti) has been replaced by the layman.

Today’s audience for Bharatanatyam is cosmopolitan, even international and completely heterogeneous. Yet, in all these groups, there is very little understanding of the dance’s delicate nuances; all come to view the dance for divergent reasons.

Among these reasons one can count the following: people go to watch a dance only if the performer is a “known name” or there is some controversy surrounding the artist/ artists/ event. Or else the event is attractively packaged – either a fancy title, or some other marketing gimmick is often employed to woo the layman. Or else it becomes an event – a well-known festival, or a star chief guest who can pull in the crowds. Some go to be seen and maybe – enter the recently deified Page-3! Or if all else fails, the dance is the stick before audiences reach their carrots – either cocktails or dinner. This frankly is why audiences today go to see classical dances. Very few go to enjoy the ananda or the rasa of a performance.

How does this impact the dancer and her dance? First, this means that each dancer has to develop her own niche audience for her art. There is no natural audience for the art. In the absence of professional impressarios, the dancer often has to undertake all this marketing and packaging herself. Very often organiers ask dancers as to what “new piece” they will be presenting. They do this since they know that only the “new” can ensure at least some viewers. Thus, most often repackaging is renamed innovation and the audience is treated to more of the same without any generational progression in the art form.

The other impact of this new kind of audience is owed to its illiteracy in dance. This leads dancers often to launch lengthy explanations before each item so that the audiences can understand the precise thoughts and motifs behind each number, even though the intricacies of the piece still remain in a hazy domain. So beyond the traditional skills learnt from a guru by way of a classical dance art form, dancers have to increasingly hone their communication, PR and marketing skills and market themselves as viable market commodities that audiences are led to “choose” to “prefer.” The classical dancers’ appearance in various “style and leisure” columns in the media (especially in the burgeoning newspaper supplements and in the hair-cutting salon brand of magazines) is an offshoot of this compulsion of the dancer to make herself known not merely as a dancer but as “someone” — a personality or a dancer plus.

This kind of audience illiteracy also impacts the content of the dance. How very often in the recent past have I not been able to perform a varnam in its entirety or — even when entire – am forced to truncate the sancharis. The short attention spans of audiences – and they are reducing virtually by the day – ensures that manodharma (creative improvisation) in this live art form is curtailed. Also, today there is probably no natural audience for the slow and detail laden “padams” and “javalis” which provide valuable texture to the dancers’ craft and testify to her merit. If Bala Saraswathy performed padams that seeped to the very soul — and young dancers are often told that her art was magical — it was as much because she had the abundant rasikas who enjoyed her delineations and every inflection of her expression.

Today, if the slow is eschewed, it is increasingly being replaced by the jazzy, the glamorous, the fast, and the rhythmic. Pyrotechnics enshrined in long never ending jathi sequences, expanded for aural impact, often do not contain adequate “stuff.” Yet they garner approval from our illiterate audiences of today. Audience scholarship does not exist anymore. That is the terrible lament of artists today.

Also, the venues for today’s Bharatanatyam have grown from the narrow dark cubicles of the temple or chambers in the homes of dancers to large prosceniums to accommodate larger audience numbers to make performances viable. This too alters the dance and from an intrinsically inward looking art form, Bharatanatyam today has become centripetal; its energy dissipating.

The audience of today also brings to Bharatanatyam their confusion – how do they perceive such an art? Is it ritual, entertainment, performance or a heritage artefact? Such confusion pressures the artist to continually justify their art form in today’s contexts. Bharatanatyam is seen as archaic and quaint. Not as a medium of communication that can convey beautiful and other images through its highly evolved language of expressions. This constant lack of organic legitimacy hampers the growth of the dance.

While state agencies and private organisations invest in programmes for many reasons, not many have launched any sustained campaign to improve the quality of the dance’s audiences. The hurried and rampant populist mania to learn classical dance somehow does not translate into rasikas for the art.

Learning is restricted to the classroom and may be a few performances by the student. Here, I would like to raise the collective failure of the teachers of Bharatanatyam as well. Dance is a performing art. Strengthening the visual vocabulary of students is extremely important. Dance teachers, by and large, do not initiate or encourage their students to go and watch other dancers even while they are learning. This is their failing.

What happens to those thousands who have learnt dance, presented arangetrams and spent money on acquiring the glamour of the dance? What prevents them from at least being eclectic and informed audiences? Where does their love for the art go? These are questions for which no easy answers can be found.

(The above is an expanded version of thoughts penned by the dancer some time ago; Geeta says that she feels even more strongly about the issues than when she first wrote it!)

*

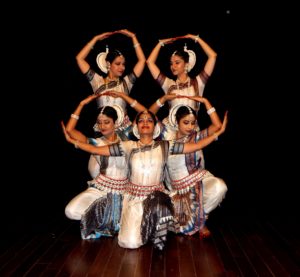

A celebrated artiste and star-performer, Geeta Chandran in her dance skilfully weaves abstract notions of Joy, Beauty, Values, Aspirations, Myth and Spirituality. She is the founder-president of Natya-Vriksha and artistic director of Natya Vriksha Dance Company, known for the high aesthetic quality of its group presentations. She was awarded the prestigious national award Padma Shri in 2007. She is also recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for Bharatanatyam in 2016. In her effort to “en-dance the universe,” she engages in a strategic range of dance-related activities: performing, teaching, conducting, singing, collaborating, organizing, writing and speaking to new youth audiences.