“Attar compels you to confront yourself, strip away illusion, and walk your path”

Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

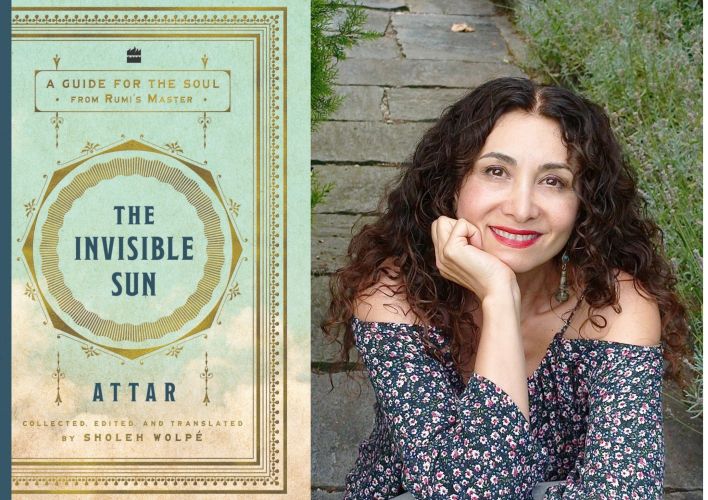

Iranian-born Poet-Playwright Sholeh Wolpé works have long illuminated the bridges between cultures, languages, and spiritual traditions. Her latest bookpix, The Invisible Sun (HarperCollins), offers a luminous translation of Attar of Nishapur’s works. One of Persian literature’s most profound mystic voices, Rumi revered Attar.

In conversation with Life & More, she tells us how deeply Attar’s works have impacted her, as also her process of translating Attar’s works. Excerpts:

What first drew you to Attar. How did you pick and choose his poems for translation? Did you follow any method or picked up just what appealed to your heart.

The 12th-century Iranian Sufi mystic poet Attar is, in my opinion, one of the most important poets and thinkers of our world. I first encountered his work through his masterpiece The Conference of the Birds, an allegorical epic about our human struggle — both physical and spiritual. It is a brilliant, engrossing narrative filled with beguiling parables that guide, instruct, and entertain.

Attar’s use of everyday stories and historical chronicles as vehicles for metaphysical truth was a technique he pioneered—one later adopted by Hafiz and Rumi.

I spent several years translating — or rather, re-creating — The Conference of the Birds into a work that could speak to modern readers while retaining its poetic soul. I gave it my heart and soul, and in return it changed both. The poem is a guide to the journey of the soul. It unites rather than divides; it does not champion any single creed. It simply lights the way so you can see.

Since its publication in 2017 (by W. W. Norton), it has inspired countless artists, musicians, and seekers. But it is a book that asks for commitment—you must follow the story to its end.

When I began The Invisible Sun, I wanted to assemble a collection of Attar’s verses that readers could open at random and find soul-stirring wisdom. I selected lines that moved me most. There were many—it was difficult to choose. Perhaps more collections will follow.

How did The Invisible Sun come to be — as a translation, but also as a personal calling?

Bringing Attar’s voice into the world through a poetic re-creation has been a personal mission because—well, look around! Our world is in dire need of his words. His wisdom transcends religion, geography, and time. He speaks directly to the soul. His metaphors are cosmic yet intimate, never bound to dogma or belief. Whether you call the Divine God, Allah, Jah, or simply the Universe, Attar’s words reach you.

He compels you to confront yourself, strip away illusion, and walk your own path. That is universal. Whether you are in Delhi, New York, Beijing or Tehran, the call is the same: purify the heart and begin the journey.

The title The Invisible Sun is deeply evocative. What does this “invisible sun” signify for you — spiritually, emotionally, or poetically?

The title comes from one of Attar’s poems where he tells us there is an invisible sun hidden within each of us, awaiting revelation. He does not exalt one group above another; he reminds us that we all carry the sun inside because we are mirrors that, when turned toward the Divine, can reflect its light and become one with it.

This reflection is not perfection—only the Divine possesses perfection—but we may share its attributes. Attar warns us to keep the mirror of our souls free from the dust of prejudice, cruelty, and ego, or else we will remain only potential light-bearers who never know the Divine, never experience its attributes.

You’ve described translation as “writing between worlds.” How do you balance fidelity to Attar’s Persian with the need to let the English breathe as poetry?

Translation, to me, is an act of re-creation. Persian poetry is musical, metaphorical, and layered with cultural allusion. Literal translation cannot contain its essence. I had to absorb the music and intention of Attar’s verses to re-create them in English without losing their soul.

I did not hesitate to use contemporary phrasing when it carried the original spirit. I wanted readers to feel the poems in their bodies, not merely read them with their minds.

What kind of challenges did you face while doing this translation, and how did you overcome those? Any particular portion that was especially difficult to translate?

Every verse demanded everything. You must cut to the marrow of each line—feel it, understand it, verify it through scholarship—before you can begin re-creation.

Persian is a language of ambiguity and grace, and Attar moves through that space with mastery. He uses multiple words for “self,” distinguishing between the ego-self and the soul, which required precision. And because Persian lacks gendered nouns and pronouns, I had to resist English’s impulse to gender the Divine. That demanded restraint and attention to resonance as much as accuracy.

You are a poet yourself. Did being a poet help translating Attar’s works?

Absolutely. Translation is an act of poetic re-creation, and I could not have undertaken it without being a bilingual, bicultural poet who writes in English. Only a poet can reimagine a poem so it breathes naturally in another tongue.

What were your different experience while you were translating? Did you feel, any time, that were in dialogue with Attar — or collaborating across centuries?

Yes, constantly. Entering his poetry felt like stepping through a portal into a timeless realm where meaning alone exists. It was surreal, beautiful and addictive.

Attar’s work explores the annihilation of the self, divine love, and the journey toward unity — ideas that may seem distant from contemporary life. How do you explain his mysticism to today’s readers?

It isn’t distant from the contemporary life at all. On the contrary, it is more relevant than ever. “Annihilation of the self” does not mean destroying our bodies or lives—it means detaching from illusion. Attar urges us to excel in all we do, but not to cling to what we do. Not be attached.

And when he speaks of unity, he does not mean uniformity; he tells us that unity is possible only through diversity. How is that not relevant today? In fact, it is something we are still yet to learn and practice. And when he calls the ego-self “that cyclone of calamities,” how could that not speak to this age of self-adulation and power-drunk leaders?

Persian poetry carries immense musicality and rhythm. How did you approach preserving that sound in English — especially given that the two languages move so differently?

Each language is its own universe. When you translate, you relocate the poem from one cosmos into another. You can either deliver a corpse or a living poem. I strive for the latter. That’s why a translator of poetry must be bilingual, bicultural, and a poet in the target language. Only then can the re-created poem breathe, live, and sing anew.

Much of your own work — from The Conference of the Birds stage adaptation to Abacus of Loss — engages with exile, displacement, and belonging. Is The Invisible Sun like taking a break from that?

Not really. Attar teaches that pain is the crucible of transformation. To reach the Divine shore as a pure drop and merge with the ocean requires motion. Pain, in this sense, is not merely physical—it is the pain of seeing clearly, of relinquishing illusion.

He tells us to empty our cups of belief and disbelief alike so we may receive. That emptying hurts. The journey may require exile, because not everyone will understand it. To seek truth, we must let go of belonging. When you become one with the Divine, the words “exile” and “belonging” lose meaning.

Is Attar still relevant today? Do you think today’s generation can identify with him and his works?

Is he relevant today? I’d say, more than ever. Readers of The Invisible Sun will feel seen, shaken, and transformed. Attar’s wisdom is the culmination of many ancient wisdoms; it is not about dogma but soul-truth. His words melt fear, ignite joy, and remind us that we are divine mirrors—capable of radiance through love, pain, and grace. Through Attar’s voice, I hope readers begin to hear their own.

Any lines from The Invisible Sun that hold special meaning for you?

I love them all, but here is a favorite:

You are standing at the foot of an invisible wall

and what you see is nothing but your own shadow.

Smash the wall, step through.

Both worlds are treasures in your pocket.

In other words, don’t be deceived by illusion. Social media, AI-generated noise—all these distractions are but shadows. The wall must be shattered, or we remain trapped, drowning in our own reflections.

Any more translations from you coming up? – Attar’s or any other Persian or Urdu poets?

I work primarily as a poet, writer and librettist. My memoir in verse Abacus of Loss (University of Arkansas Press) has just been re-published as a bilingual English–Spanish edition by Visor Libros in Spain. I am also completing a novel about a remarkable Iranian poet and leader.

As for translation, I will certainly return to Attar and perhaps include other ancient Iranian masters. It is a labor of love—and love is something I have in abundance.