Pushing Gods Out is a satire that opposes peoples’ interpretation of religion

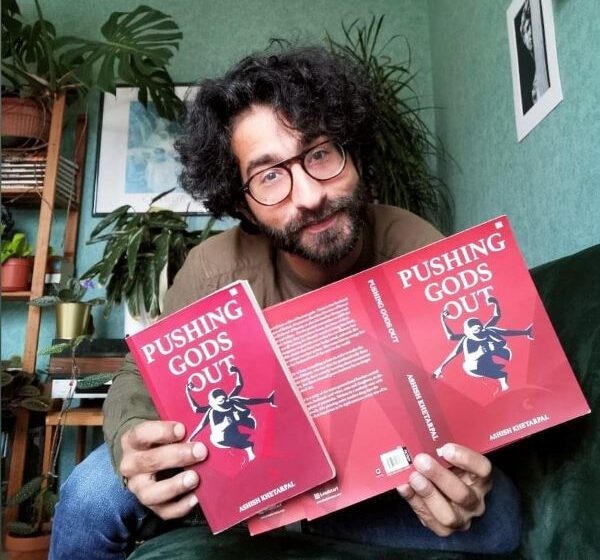

Ashish Khetarpal with his recently published novel Pushing Gods Out

Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

Born in the ancient city of Meerut in western Uttar Pradesh (India), into a humble, middle-class family, Ashish Khetarpal had an ordinary childhood. Meerut, he says, during his growing up years was not a very peaceful city to live in. The experience of the disturbing incidents happening on a regular basis in the strife-torn city didn’t leave him even after he left the city and the country for France. As he says, “The city’s stories stayed with me like unwanted luggage, piled in a corner. And in this book, Pushing Gods Out, I have, mingling fact and fiction, tried to unpack some of those.”

Pushing Gods Out is Khetarpal’s first novel (though he has written poems and short stories earlier), and tells the story of the trans-generational burden carried by people in a patriarchal society. The author who presently lives in Rennes, France, tells us more about the making of the book:

How did you come up with the idea of such a plot?

Back in the year 2018 when I had decided to write a novel, I worked on the storyline for about four months before finally sitting down. I remember the day vividly; it was the afternoon of May 4. With all my notes neatly arranged around me, I opened a fresh document on the computer. Nervous as I was about making a grand opening, the very first sentence seemed to be betraying the said storyline. It was a long Proustian sentence forming a paragraph on its own. I obviously thought of erasing it and starting afresh. But instead, I typed on, having turned it into a writing exercise where I would stop when it would no longer be possible to go any further.

In my mind, it was simply a playful digression, I still had my other story sitting next to me, and I had every intention of going back to it. Long story short, I never did.

Pushing Gods Out started as a writing sport. After I finished the first chapter (The Toy Massacre, TTM), I did not know what to do with it. I wrote it in one very brisk moment of catharsis, but it was not a novel, or a novella. Once again, I thought of returning to my planned storyline, and told myself that maybe later I would add some more fabric to TTM and, one day, publish it as a novella. But this did not happen either. And it took me six months before I could come back and write the second chapter.

The plot sort of threw itself in front of me in several fractured phases over the next few years. Having grown distrustful of carefully drawn-out storylines, I wrote most of the first half of the book without any particular plot in mind. I simply followed the characters, and they grew on their own, said and did things I had not prepared at all. The second half, however, was much more planned.

Why bring in a revered name (Lord Rama) to churn out a fiction?

Be it in India or elsewhere, there is no denying that cultural names carry a certain weight, and sometimes this weight can transform into a burden for the carrier. While working on the first chapter, it occurred to me that every actor in Bollywood who has been given the name of Rama was also given his virtues, and a path littered with villains in order to test the said virtues. And Rama always succeeded. A hero with the name of Rama cannot be defeated, is the message. The same is, in my estimate, also true for some other names such as ‘Lakshman’, ‘Sita’ etc. If you think about it, these are not simply names, but bold value-personifications imbued in the daily life. This interested me as much as it disturbed me, and I decided to make it the underlying theme of the book.

While Shanti wants Rama to avenge her, what is your explanation for Rama not wanting to come out?

I took the aforementioned theme and put it on its head: not everyone can stand up to the lofty standards of his name; for once, the unborn bearer of Rama’s name is not sure if he can carry out the exacting task of avenging Shanti, and therefore hesitates being pushed out into the world. It is a biological truth that babies are sometimes born with physical flaws, but to imagine even before its birth that it will have the virtues matching those of the very Lord is undoubtedly a humongous burden.

What message do you want to convey to the reader through this story?

First and foremost, I should like to reiterate here that the book is written as a satire, and should be read bearing this detail in mind. I’m not rallying against religion but peoples’ interpretation of it.

First and foremost, the book is an attempt to understand for myself the role religion can play in everyday life. It is borderline reverie to think that religion is all good, just like it is plain cynicism to think it to be completely evil. Then, there is no denying that, like any other country, ours have its own problems. And religion has some part to play in it. The long book is my invitation to pool some of those problems and perhaps look at them differently.

For example, it revisits the woman’s condition in our society: Shanti is too devious, Rampyari and Kaikeyi, too oppressed; Hira is too bold, Lalita, too promiscuous, but Mala can never be too religious. Then, there’s the flip-side. More is given to boys in terms of care, affection, and opportunities. But is it for this reason that we expect more of them in return? Or, is it because we expect more that we give more? Either way, we know there is an imbalance, and it is not good for either of them.

The book is, I believe, a facetious account of the workings of an average middle-class Indian family; it is, in addition to this, a glimpse into this trans-generational inheritance as a source of burden for the earthly Ramas who did not ask for the name and cannot boast of His virtues.

This is your first novel. What made you transform into a novelist from a poet?

Ever since I was in school, I had wanted to write a novel. But I needed to hone my skills, read a decent number of books, feel a bit confident, but mostly, wait for a story that would keep me interested long enough to write about it. I took a break from writing poetry in 2017 when it was brought to my attention by someone who had critiqued my book of poems that I needed to update some of the literary tools I employ in my writing. I agreed with the person, though I do hope to publish more poetry in the future.