‘Instruments of Torture’ is inspired by real people, says author Aparna Sanyal

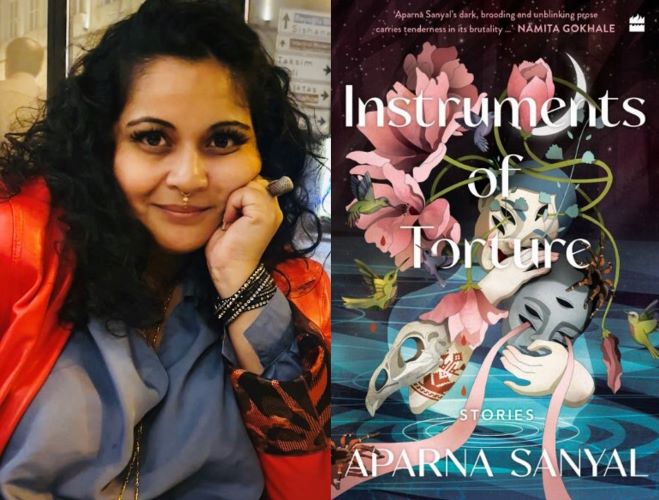

Author Aparna Sanyal and her book, Instruments of Torture

Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

Descend into the deepest, murkiest torture chambers of the soul with Aparna Sanyal’s. Instruments of Torture (HarperCollins), a collection of eight short stories, each of which explores a different theme. Each of the eight stories is named after a medieval torture device, and the true meaning—and impact—of every title bubble to the surface as the connection between the instruments and their psychological counterparts are revealed.

The Rack showcases how an anguished man is being drugged with hormones to ‘cure’ him of dwarfism; The Judas Cradle talks about a forbidden love affair while in The Pillory a man is reunited with his first love at a strange place.

A thought-provoking book that jolts you inwardly is what this book can be summarised as in one sentence. Life & More speaks to Sanyal to gain more insights into it:

What inspired you to write Instruments of Torture and delve into such a morose and difficult subject?

A few years ago I visited a travelling exhibition of medieval torture instruments. It was a sobering but illuminating experience, seeing close-up these physical torture devices that had been used at some point in history. The idea came to me then—to collate the brutality of these physical torture devices to trauma caused by emotional and mental abuse, kinks and deviances— and to set the stories that emerged from this juxtaposition in the modern world.

What sort of research went into the book? Were there any particularly challenging or emotionally taxing aspects of this process?

I read about different torture devices and their historical usage in some detail. This was heavy reading, but it didn’t discourage me. On the contrary, it made the stories and the characters who carry them on their shoulders, clearer in my head. Of course, as these characters became themselves, there came the inevitable attachment and investment in their fates. And this is always an emotional journey for me.

Are these stories based on real incidents, are inspired by real incidents or these are purely fictional and a figment of your imagination?

The stories are fictionalised outcomes for real characters I’ve known or observed closely in my life. So, I’ve carried a very clear physical and mental picture of each protagonist in my head, while knowing how different their real life character arcs are. Essentially these are the people who I’ve looked at closely and wondered, ‘what if there were a different set circumstance in this person’s life…’ and gone from there. One of the characters is me. Care to guess which one?

How challenging was it writing these stories, and once you decided to do so, how much time did you take to complete the book, cover to cover?

There is a time for a story to live in my head, and then there is a time for it to translate to the page. I live with the story for far longer than I should: there are times I’m lost for hours, perhaps just completing a chore or reading, but there is a second track constantly in my head, where I’m worrying out some plot point or thinking deeply about a character. I have a prodigious ability to be lost in my head. Then, when I do sit to write, the story comes out semi-formed but in very rough wordage. This collection took about 2 years to coalesce in my head, 3 weeks to get to first draft thereafter, and then 6-7 edits over the span of almost 2 years before I felt it was anywhere close to ready.

In your opinion, what have been some of the most effective psychological tools employed alongside physical instruments of torture throughout history?

Psychological torture is effective and ever present. Although we may choose to look at overt tools like the mind control and LSD experiments of the CIA in the 1950s, brainwashing in Nazi Germany or even the systematic dehumanisation of colonised or marginalised peoples across history, the world is suffused by people and institutions that use psychological tricks and mind control in everyday life. For example, even gaslighting is a form of psychological torture that women undergo almost daily in a patriarchal society, where their importance, worth and dreams are undermined in an almost banal way. The ‘banality of evil’ is a concept I’m currently fascinated by.

Do you think that the study of torture and its instruments contributes to our understanding of human history and psychology?

Absolutely. Pared down to our base, animalistic selves, our true personas are revealed. The way in which a nation expresses oppression and violence towards another informs the discourse on who that nation and its people are in that place in time. It is an insight into mass character that a time of peace would rarely provide.

Torture is used as a means of social or political control rather than solely for extracting information or punishment. Your take on that.

I believe that mass torture is primarily an instrument of control. No matter whether it be physical or psychological. Yes, in war and, say, espionage or crime, it is used to extract information, or as express punishment. However, we are either scared, or too inured, to talk about the everyday political, institutional use of methods like sanctions, marginalization, isolation, or even caste-violence, for example, to systematically control a population.

What role do you believe the depiction of torture in media and popular culture plays in shaping public perceptions of its history and use?

Some depiction may be gratuitous, some may be oblique, and some may be inferred, like in my book. But no matter how glamorised or pared down the description of the act, media informs life, just as life informs media.

In your book, you explore the ethical implications of studying and documenting torture. How do you navigate these ethical considerations as a researcher and author?

I’ll answer this question the way I understand it, which may seem oblique to the way it is asked. But this is the answer of utmost importance to me. It is imperative for me to deal with each character and instance in the book with respect, without co-opting or appropriating their experience. It’s a delicate balance and one I’m acutely aware of. I can only hope I haven’t crossed any ethical lines and if I have done so, I am open to make reparation and learn.

Are there any parallels or connections between historical instruments of torture and contemporary practices of interrogation or punishment that you found particularly striking?

I haven’t studied contemporary practices in detail enough to have a satisfactory answer to this question.

Finally, what is your target readership with this book?

Anyone over the age of 16, who wants to read out of the box, who enjoys reading about the ‘why’ of our behaviour, and has an open mind.