It was a Wednesday. Assistant Police Inspector Tukaram Omble was scheduled to work the evening shift. The television was tuned to the cricket match—India was playing England in the fifth ODI of a seven match bilateral cricket series in Cuttack. Before he could leave for the DB Marg police station to report to work, the cricket buff checked the score on the television. Even afterwards, he kept calling home to get an update on the score.

‘He had called at least twice or thrice to ask for the score,’ says Vaishali, third of Omble’s four daughters. ‘But after 9 o’clock we heard that something had gone wrong at the VT (CSMT) station and at the Taj Hotel. When Pappa called again, I was a bit irritated. Ata jinkli na India? Parat parat kai phone kartay (Hasn’t India won now? Why do you keep calling)? I said. But then he told me that there was an attack in South Mumbai. He told me, my mother and my sisters to stay indoors.’

When she asked him how the situation at DB Marg police station was, he said nothing had happened in their area until then. And then, fully familiar with her father’s alacrity in staying at the front at all times, she cautioned him, ‘I know you are in the habit of staying at the front but please be careful,’ she said. He told her he would.

After that, calls made to his phone went unanswered. The moment that made him a national hero was not witnessed by his family. They would be told later that he had made the ultimate sacrifice, making sure even as he braved bullets that one terrorist was captured alive on the night of 26 November 2008. About 5 km from where Omble died, his wife and daughters waited for his call. And in the years since they continued to live in the long shadow of the night when he never returned home.

That this martyr’s village hasn’t forgotten him is immediately apparent upon driving into Kedambe, a village of about 250 homes separated by paddy fields framed by lush hill slopes, 284 km from Mumbai. A banner bearing the photograph of Assistant Police Inspector Tukaram Omble who was killed while capturing terrorist Ajmal Kasab is at the entrance to the village where he grew up, and where his heart always was. ‘Shaheed Tukaram Omble’, it says, a daily reminder of his martyrdom.

In the primary school where the policeman was once a student, children tell the story of their intrepid hero and his ultimate sacrifice with as much ease as they sing a powada, a traditional Marathi ballad, in praise of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj outwitting Bijapur noble Afzal Khan, a story that has found renditions in Maharashtra’s folk music for generations.

In the classroom, the question, ‘Who was Tukaram Omble?’ is met with an array of answers, all correct. ‘He was a policeman,’ there is a chorus. Standing among the group of powada singers is ten-year-old Swanand Omble, son of Omble’s cousin Ramchandra. He says in a voice barely louder than a whisper, ‘Majhya kakanni Kasabla pakadla (my uncle captured Kasab).’

That night in 2008 when Swanand was only a few months old, Tukaram Omble, then fifty-three years old, was in a police bandobast near Girgaum Chowpatty, Mumbai’s most iconic beachfront. Wireless messages had said two armed terrorists had carjacked a Skoda sedan and were speeding in their direction. When the car stopped at the bandobast on the mostly deserted road past midnight, Kasab stepped out of the passenger side, his AK-47 pointed at the waiting policemen. Omble threw himself at Kasab, taking a spray of bullets even as he tackled the terrorist to the ground, his sacrifice leading to Kasab being captured alive, and setting the foundation for a long investigation and judicial process that could clearly pin down the conspirators across the border.

But the fact that memories of his bravery live on in the minds of students, many of them born after he was killed, is in itself a special tribute to Omble, who was extremely fond of children.

At the time that he joined the Mumbai Police in 1979, Omble had let go of a job opportunity in the Brihanmumbai Electric Supply and Transport (BEST) undertaking. Drawn to the uniform since he was a boy grazing his cattle, he had always looked up to his maternal aunt’s husband, a driver with the Indian Army. Eventually, for the young man who once sold jackfruits and mangoes in Kedambe, the road through the Sahyadri hills out of Satara district to Mumbai was the one that would lead him to his uniform.

It was a proud day for his joint family in the scenic village when he came back as a Mumbai Police constable or, as they still fondly call him, ‘hawaldar’. He was the first from his village to don the khaki uniform, but in the ten years since his martyrdom, many more have signed up for jobs as policemen.

Prakash Omble, Kedambe’s deputy sarpanch and Omble’s first cousin, says, ‘He was the first policeman in our village. Since 26/11, there have been thirteen others. Six are posted in Mumbai, four in Pune and some others in the Border Security Force (BSF) and the Indian Navy. A memorial to him in our village continues to inspire the youth.’

Septuagenarian Sulabai Shelar is Omble’s niece, but she has memories of them growing up together. ‘He would bring so many chocolates every time he came visiting from the city,’ she says animatedly. ‘And he would give them to all the kids in the village.’

Back in Mumbai, Omble’s daughter Vaishali also reminisces about her father’s love for children. In a way, he was the Pied Piper of the police residential quarters on Sir Pochkhanawala Road in Worli. ‘Whenever he came home after work in the evenings at least two or three kids from the building would follow him home. He was very popular among them,’ she says. Minutes later, a neighbour drops off her two-year-old daughter at the Omble residence, the toddler making herself at home almost immediately, finding a cozy corner on the sofa for a quick nap. Their home, Vaishali says, is still accustomed to the presence of children. ‘Whenever he had a chance, he would buy food for street kids. He loved children and everything he did for them came straight from the heart,’ she says.

In Kedambe, the primary school children look up to Omble. Chandrakant Jadhav, a teacher in the Zilla Parishad School in Kedambe says, ‘When we tell these children about patriotism, in Omble we have an example from home.’

The kids may be unsure whether Omble, then attached to the DB Marg police station in Mumbai, nabbed Pakistani terrorist Kasab at Marine Drive or the nearby railway station Marine Lines. But if it was not for Omble’s bravery, they believe, Kasab would not have been caught alive. About that, they are absolutely sure.

The village primary school ground has almost all villagers in attendance on days of national importance such as Independence Day and Republic Day. On many such occasions, Tukaram Omble was present with his wife and four daughters, his family remembers. In the decade since his passing, the village has one more important day to observe, its own hero to remember.

‘There are three days that are very important to us— 15 August, 26 January and 26 November,’ the deputy sarpanch says.

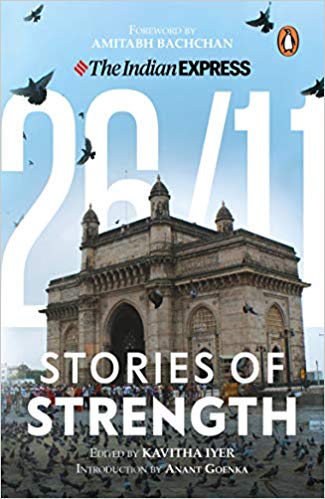

Excerpted with permission from 26/11 Stories of Strength by The Indian Express, Penguin Random House