Rajkumari Sharma Tankha

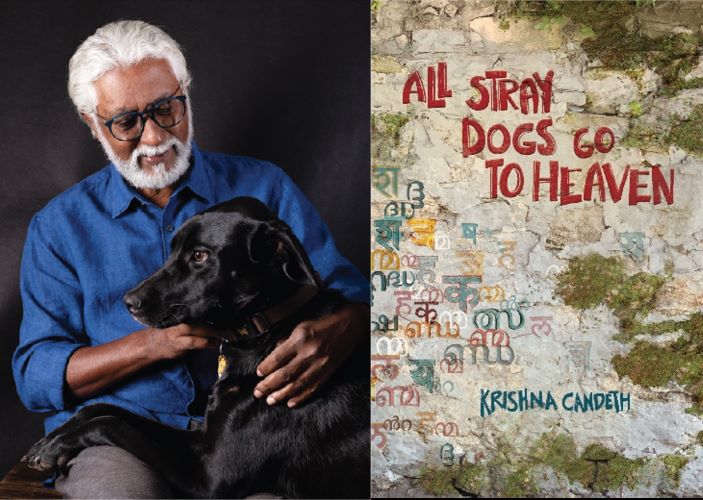

All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven (BluOne Ink) is a debut novel by filmmaker-cum-poet Krishna Candeth. The book by the Kerala-born, Colombia-based author is an interesting tale of love and friendship, dreams and reality told through multiple perspectives to keep the reader glued to it. Excerpts from an interview:

When did the idea of penning this book come and how did you go about writing it? How much time did it take to complete it, cover to cover?

In the Preface to the novel I talk of how the effort to raise money for a film is vitally linked to a peculiar but necessary talent called bullshitting. We all carry with us some version or modification of this blessed talent but it takes some of us a very long time to realise that the version we possess is hopelessly inadequate to fund the project at hand. It was during one of these lulls of fundraising that I decided to ditch the film project and write a novel instead.

I suppose I’ve carried bits and pieces of the novel in my head for a very long time. And it was naturally those bits and pieces that I first fleshed out when the time came to write it. Since the structure of the novel is episodic it was then a question of finding the thread that would run through certain episodes, through the past and future, and through the moods and feelings of the characters. As for the time involved, it took me a little over four years to write it and around the same time trying to get it published.

All Stray Dogs Go To Heaven is quite a peculiar title… On a lighter note, if all stray dogs go to heaven, where do the others, the pet ones, go?

I’ve spent a lot of time observing stray dogs on the street. Some of them have a fine veneer of confidence and spend their time trotting purposefully from one venue to the next while others are perpetually on guard for fear of being screamed at or abused. Once, I was shooting a documentary in Varanasi – it was a few minutes before sunset and the light was honey thick and perfect. An old man was seated on the top step of the ghat and below him two boats were crossing in the late evening light. Just behind him four or five stray dogs were stretched out and fast asleep. We set up our camera behind the dogs and were about to film this scene of great calm and serenity when the owner of a tea shop came rushing out of his stall shouting and waving a stick and chased all the dogs away. When I asked him what had prompted him to do that, he said all he was doing was to make sure we got an acha shot with all those stinking street dogs out of the way!

The title of stray dogs might well apply to a lot of the characters in the novel – they wander around not in the alleys of a city but in the back streets of their own imagination. As one of the characters in the novel says, they may have a roof over their heads but they don’t have a roof over their feelings.

As for domestic pets, it’s a very fine line between pet hell and pet heaven! A lot of pet owners act out their own caprices and fantasies on their pets, dressing them up in conical hats and sunglasses and booking professional grooming services and buying fancy birthday treats. Or conversely, in a fit of hurt or anger they decide that their pets need to be sent off for a bit of training and disciplinary action. Or even abandoned or banished forever to some adoption agency.

What’s your take on gender inequality in patriarchal Vs matriarchal society? You talked about matriarchal society in your book, despite which women are still being discriminated against. What kind of changes have you seen in the 20 years so far as this aspect is concerned?

It is unfortunately true that even though the Constitution guarantees equal rights for both men and women, women suffer huge gender disparities in India and continue to be treated as second class citizens. They have less access to education and employment but what needs to be emphasised is that the vast majority of Indian women believe they should be subservient to men. This, obviously, is the principal effect of having lived so long in a patriarchal society – they simply don’t have the awareness or the vocabulary to talk about their rights or what they must do to achieve some degree of equality.

The systematic problem of patriarchal society in India continues to be the same- the acceptance and, in many instances, the condoning of incidents of domestic and sexual violence.

The society depicted in the novel is not matriarchal – it is matrilineal in the sense that descent and inheritance of property is traced through women. In both patriarchal and matrilineal societies it is clear that it is the women who have a huge influence in overseeing the day-to-day running of the house as well as decisions concerning social and family events. But there’s a twist – even though women are afforded great honour and respect it is the MEN who make the bigger decisions and run things outside the home.

Although one may point to some changes in the status of women, it has, in most parts of the country, been nearly non-existent or appallingly slow. It is disheartening to think that even in Kerala where women have successfully achieved parity in education, the State still has, by some estimates, the highest unemployment rate for women in the country!

You have made short films and documentaries and have now written your first novel. How has been the experience of dabbling with a completely different medium from the one you have done before?

I think that on one level, the difficulties in both mediums are very similar – the decision of what to show or not show in a film, and the corresponding decision of what should be left unsaid in a book. In both books and movies, readers and viewers are manipulated by how and how much information is handed out to them. Since this is how the narrative is traditionally carried forward much of its effect depends on what the author or director chooses to include or leave out. It is not something that can be easily learnt; it comes slowly from a sense of being able to feel the pulse of the novel or film and carry its tone and texture with you at all times.

I like to see both novels and films take their time, expand and accumulate, rather than fulfill the expectations of certain readers or viewers and run off towards some arbitrary or pre-conceived destination called The End.

This is your first attempt at writing at the young age of 70 – we do believe creativity is beyond age and numbers. How satisfying has been the experience on personal and creative levels?

Hugely satisfying. Although I had written and published some poetry before, this was my first attempt at extended writing. It was especially satisfying because I’ve always had a childish tendency to leave things half-done and go running after some new project that has attracted my attention! To concentrate and persevere day after day for more than four years and bring the novel to a desired end has been something I think I can be proud of.

Who has been your inspiration as an author and as a filmmaker?

All artists carry within themselves a world of imagination and experience that is their own and wouldn’t exist without them. So their primary responsibility is to make that world, through their style and narrative capability, accessible to their readers and viewers. We may be open to all kinds of cultural influences but we must find a way of adapting those influences to our own rhythms and forms of storytelling. Otherwise, we may end up with something that is formal and turgid, a form and a way of seeing that is cut and pasted onto a culture where it doesn’t belong. I may admire the films of Ozu and Kurosawa and Orson Welles, Bresson and Fellini and Paradjanov but I must find a way to mould those diverse influences into a form of muscular storytelling that reflects my own upbringing and temperament. That really was the genius of Satyajit Ray – he was influenced by many directors but when it came to making his own films he put all those ideas to one side of his head and forged a style and narrative shorthand that was his very own.

The thing about novels that appeals to me is their wonderfully elastic form. Novels are not written as the crow flies. They accommodate everything! I like novels that digress and snake around, talk about all kinds of things, and are not always obsessed with advancing the plot.

I know there is something that has to be uncovered or discovered while writing a book even though I don’t know what that is!

Two books that affected me greatly when I first read them many years ago were Milan Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being and Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude.

In his novel Kundera talks of how characters are born not of a woman but of a sentence, a situation, a metaphor that carries in a nutshell unexplored possibilities that the author believes don’t exist anywhere else.

The great authors have an admirable facility for both invention and narration. They tell a story and, at the same time, they turn the story on itself: they enrich the narrative by subverting it. It’s an old trick. Lava and Kusa turn the epic on its head by reciting the Ramayana in the court of their father, Rama.

How different is filmmaking in the US or England vis-à-vis India, in terms of technological advancements and support?

There used to be a time not too long ago when Indian directors took a sort of easy pride in saying that the films they showed at festivals more than made up for their lack of technical expertise by being rich in character and storytelling. We now seem to have come full circle – our films are glossy and technologically on the money but we seem to have lost some of that appetite for real feeling somewhere along the way.

In any case, it is a misnomer to call what they make in the UK or the USA these days FILMS. Strictly speaking, they are not Films at all because most films today are made electronically. Instead of a magazine being loaded on to the camera a card is inserted that electronically records whatever the camera is instructed to see. Even though some directors continue to use celluloid, they’re finding it more and more difficult to find stock, and most of the labs in England and the United States that used to develop and print film are fast going out of business.

The latest iPhones, I’m told, offer a “cinematic” option which Apple claims, resembles old-fashioned film. What a pathetic and melodramatic end to the glorious art of shooting, editing and projecting real films!

What do we expect next from you – a film or a book?

I like working on poems because they are portable and you can carry them quite easily around in your head. I also make a note of ideas that could translate well into screenplays although the thought of raising money to bring it to any form of realisation is always off putting. Yes, and I am also carrying out some primary research for a novel although I am yet to work out its actual form and structure.

What do you do in your free time – if you get some that is?

I live on land in Colombia where a great number of trees were cut down to facilitate the cultivation of flowers for export. I spend a lot of time visiting nurseries in the area, getting to know about native plants and trees, and beginning the long process of re- foresting the land. It’s a fascinating process and keeps me fully occupied. I can also say with absolute certainty that there are few more pleasurable things in the world than the actual planting and cultivation of a garden.

Any message you would like to give to senior citizens out there?

Senior Citizens! What a mindlessly ugly way to describe a large section of the population!! Are teenagers Junior Citizens? I don’t know who coined the phrase but he or she must surely have a tin ear. Our language is awash with huge quantities of verbal slop. We certainly don’t need to add to it.

As far as messages go, Don’t worry too much about what OTHER people think or say. Memorise a little poetry everyday, learn a new language, try and do away with some of the old prejudices, entertain new ideas, cultivate a garden. Is the world a mystery to be unveiled or a problem to be solved? No matter. The world is a place where questions multiply and answers are scarce. Do everything that you used to do before – sing, pull legs, laugh, dance – but do it with a greater curiosity and a greater sense of your place in the great order of things.

Once, many years ago, in New York, I was sitting on the same park bench as a man who must’ve been more than 80 years old, and we got to talking a little. “I don’t do much” he told me, “but I like to hang around. It feels good sometimes to just hang around.”

I have since discovered the virtues of the fine art of just hanging around. I intend to refine and perfect it in the years to come!