Team L&M

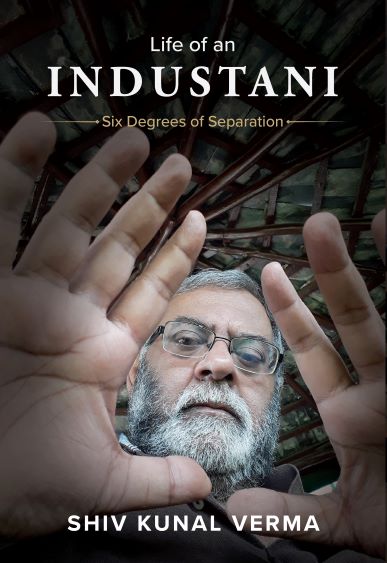

Celebrated historian and filmmaker Shiv Kunal Verma’s has come out with a new book, Life of an Industani: Six Degrees of Separation. Published by BluOne Ink, the 500-page action-packed thriller-like read is regarded as a book that is less autobiography and more a contemporary look at Indian history through the eyes of one who had lived life to the hilt.

Following is an Excerpt from the book:

On 2 October we moved from the Dibrugarh area (Chabua and Mohanbari) to Tezpur. By now it had almost become the pattern for the crew to move by An-32s while Dipti and I would move by the Cheetah. This gave us a greater understanding of the terrain, and since I always flew with the Arriflex ST by my side, one could film if an opportunity presented itself. After taking off from Chabua, we flew along the South Bank and at some point, the An-32 overtook us high in the sky. Then we were above Kaziranga, and in the eastern range we could see small herds of elephants and the odd rhino in the bheels. We swept over the grasslands where I had been shot eight years previously in the run in with poachers, and from the air I was showing Dipti the various landmarks.

Sid had taken control of the chopper and he moved in close to a rhino that was feeding in the bheel. The downdraft of the rotors and the noise of the Cheetah strangely did not seem to bother the animal at all, who sort of looked around but never looked up. I was by then leaning out and literally standing on the skids shooting downwards.

We then saw some elephants and moved in over them. A large makhna was out in the open in the water, and we got the shadow of the Cheetah go past him as we circled just 20 feet (5–6 m) above him. On the RT, I was constantly adjusting the helicopter’s position for Sid was having to look past Birdie and the last thing we needed was for the elephant to pull us down, for sooner or later the big fellow would look up. Having got some unique shots, I said,‘Ok, let’s get out of here…’

But Sid had seen a rhino with her year-old calf in the grass, and as we came close the grass literally parted, taking away whatever semblance of cover the female had. The rhino began to run and we stayed with her, flying sideways, filming. It was a tremendous shot and though it was tempting to hang around and film animals from this unique perspective, I did not want to disturb the area any further.

We crossed the Brahmaputra, and it was Dipti’s turn to reminiscence for down below was the bridge that was built by Larsen & Toubro which she had filmed in 1984. We landed at Tezpur and were received by Group Captain (later Air Commodore) Parvez Hamilton Khokhar who was commanding the MiG Operational Flying Training Unit. ‘You guys been buzzing Kaziranga?’ Khokhar had been the air attaché in Pakistan and obviously knew a thing or two about extracting information. Immediately I had put on my ‘who sir, me sir, no sir’ expression. Khokhar grinned and told Sid and Birdie,‘In that case you guys better get rid of the grass stuck to your helicopter’s skids!’

Khokhar conducted the briefing the next morning. I was finally going to fly in the MiG-21 and that was something I had been waiting for. Inducted into the IAF from the Soviet Union before the 1965 India– Pakistan War, the delta-wing MiG-21 with its multiple variants had been the backbone of not just the IAF, but also of many other air forces around the world. There were two sorties lined up that morning, the first a five- aircraft formation that would fly at mid-level over the Brahmaputra, and the second was to be with 30 Squadron (Rhinos) in which we were to rendezvous with two MiG-21s coming from Chabua who were to fire their rockets at the Dollungmukh firing range that was on the Assam– Arunachal border.

The first sortie was a lark, and as we unstuck, I could see Dipti filming the take-off from the side of the runway. Though relatively cramped for space, I found the MiG-21 quite comfortable to shoot from. After we landed, I moved across to the Rhinos, and after a detailed briefing, strapped up in the Type 66 once again. I was being flown by Squadron Leader (later Wing Commander) Navindra Nath Verma, and we headed east towards the confluence of the Subansiri and the Brahmaputra.

The MiG-21 had a unique characteristic. The air conditioning used to kick in only after the aircraft gained an altitude of 6,560 feet (2000 m). My overalls damp from sweat, I was looking forward to the blast of cool air, but instead we started getting roasted by a jet of hot air. ‘Damn,’ said Navindra Verma, ‘the air conditioning has got jammed on full heat.’ We debated what to do, for we could call off the other MiGs, stay low level to stop the air conditioning while we expended fuel, or just go on and finish the task. Since getting range clearance was a problem, we decided to push on. Soon the two other MiG-21s had linked up with us and they fired their rockets which I dutifully filmed. They then peeled off and returned to Chabua while we set course for Tezpur.

We had climbed up to 10,000 feet (3500 m) when it occurred to me that we were in a shallow dive. I could also suddenly see Navindra Verma’s helmet as his head seemed to be lolling over sideways. I called him on the RT, but there was no response, so I shook the stick violently which resulted in the aircraft jumping around but him leaving it. I quickly pulled back to regain the lost altitude and then called Tezpur ATC. ‘My pilot is not responding,’ I said, forgetting to give my call sign.

‘Who is this?’ asked the voice cautiously at the other end.‘What do you mean pilot is not responding? What is your call sign?’

‘Screw all that,’ I said, ‘just get the COO on the air.’ A few seconds later, obviously someone who knew what we were doing up there was on theRT.

‘Ok Kunal, what’s the problem.’ I said the air conditioning was jammed and we were roasting in the cockpit and that the pilot seemed to be unconscious. I was holding course and could see the Kameng River and the airfield. As the situation developed, I started to lose height and circle around as instructed by the voice, but just when everything seemed to be heading for a climax and a possible ejection, I heard Navindra Verma’s calm voice saying he had control. He must have been out for almost three to four minutes, during which time my entire life had flashed before my eyes. We landed without any further fuss, but once again the ambulances and fire engines lining the runway were a stark indication of just how lucky we had been. Parvez Khokhar24 would tell me later he had been with the COO when the emergency call had come in and he was impressed by the fact that I had not panicked, and my voice had been calm and in control. I told him frankly I was crapping my overalls. He laughed and said that was but natural.