Team L&M

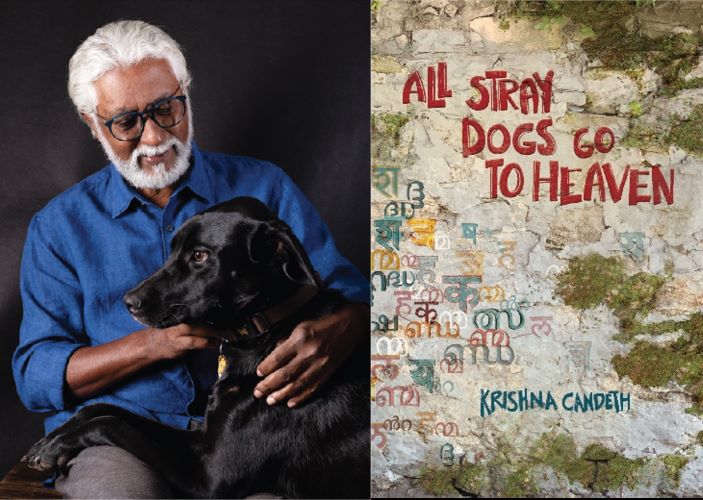

Evocative and remarkable, the stories in All Stray Dogs Go to Heaven (BlueOneInk) explore the power of love, friendship, family, as also the elusive idea of home and compels its readers to revisit their own ideas of truth, self and reality. The book is a debut work of Krishna Candeth in which he has narrated the stories from multiple perspectives, weaving past & present as also dreams & reality. Here is an excerpt (page 6-8):

This black, beggar’s bowl of a sky with not a scrap of blue for alms! A day of steady walking interrupted two or three times by thunderous rains—is this the monsoon season or are these just petulant displays of ‘western ghat weather’? I spend the night below an overhang of rock. Above me towers a shisham tree, running like a flagpole straight up to the canopy.

Early this morning, half-awake, I had the curious sensation of all the secrets inside me turning, like plants, towards the light! I close my eyes and think of how the shisham and the dense fortress of trees that have grown and spread all around it in the forest for more than a hundred years have escaped the squeeze of the human world but then I hear in my mind the treacherous tread of the elephant poachers and the sharpshooter they have hired, and I know that their greed and corruption has somehow seeped into the air above and even discoloured the forest floor. Even so, I must believe that this shisham tree will survive somehow the carelessness and greed of men.

Just beyond the screen of bamboo and ferns that have been springing up every day almost in front of my eyes, the ground runs away in a sloping tapestry of blue or purple flowers—I cannot say which—towards a spacious basin rimmed with lofty fig trees. When I had limped my way into the overhang of rock the previous night, I had no idea that just below me was this cascade of purplish- blue flowers screaming their way up and down the slope. I have just begun to feel my way through the flowery undergrowth when I hear the call of conch shells accompanied by singing and loud laughter. I slide down towards the screen of bamboo trees and hold my breath. Two elderly women with freshly woven palm umbrellas fitted neatly on their heads and elongated temple drums hanging from their necks, followed by two young women bearing clay pots, are looking up into the hefty overhanging branches of a fig tree and pointing to the black distended beehives high up in them. As they make their way down the sloping path to the bottom of the grove they begin to sing in the call-and- answer way of women transplanting rice in the fields. A few moments later the two older women begin a loud chant as they catch sight of a pillar hewed in stone deep in the circular space at the bottom of the grove, half-hidden by the spreading, ridge-like roots of a sandalwood tree. A female ancestral spirit or perhaps, the goddess Bhagavati herself, her form and aspect still commanding despite the ravages wrought by millennial winds and rains. Conscious of the gaze of the women, I make my way down and bow to the statue, then retire hastily to the shade of some trees on the far side of the slope.

One of the younger women now lights a fire under a pot raised on four large and flat stones. Her companion advances and adds many things to the pot, and I think I saw a bright milky liquid along with blood and bark and dried flowers and many powders whose names I did not know. While the brew simmers the older women strike a staccato beat on their drums, advance, fall back, and then begin a slow recitation that swells and swells until the younger women, responding to the rhythm, perform a series of swift circumambulations of the pillar; as the voices soar and the drumbeats grow more intense, they shake their heads up and down and in half-circles, falling to their knees with hands outstretched and faces close to the ground. Are they singing of the time when Bhagavati was the bold and generous mother of all living things and the anonymous benefactress of every ritual performed on earth?

When the brew is cooled and ready, it is strained into smaller pots and the women drink it down in great, bracing gulps. The two younger women, standing very still with extended arms, now begin to wail and sway, holding their hair above their necks and curling their bodies in a spate of rage and visible grief. Are they remembering the perilous time when male priests had usurped their Bhagavati’s rightful position, and brought darkness and disorder into the lives of all believers?

I am sure now that the younger women are novices, and I am witnessing some sort of an initiation ceremony. Urged on by the drums, they hook their fingers into the corners of their mouths and waggle their tongues, letting out long, stuttering wails and screaming at the patch of sky between the soaring trees. Intoxicated, it seems, by some great and absolute freedom that had been released inside themselves, they stagger toward the Bhagavati pillar and dab a reddish-black compound over the face and body of the goddess in the stone, screaming ecstatically, as if willing her to come to life, ‘She is here with me, here, here, HERE!’